« Features

Thirty Years of Travel / An Interview with Ginés Serrán-Pagán

The artist Ginés Serrán-Pagán (Ceuta, 1949) has devoted his life to his work and to the defense of human rights. He began his career thirty years ago and to date has had more than one hundred exhibits worldwide. Recently, the mayor of Miami presented him with the keys to the city in recognition of his outstanding work on behalf of humanity. A retrospective of his work was exhibited in Miami’s Wynwood Art District during the summer of 2010. ARTDISTRICTS engaged him in a long and pleasant conversation during which we spoke of his prolific life and his views on the art market, originality, and creation.

By Raisa Clavijo

Raisa Clavijo - I am aware that before arriving at artistic creation, you first studied anthropology and worked as a researcher for many years. How did your interest in art arise?

Ginés Serrán-Pagán - Indeed, my first contact with artistic creation was through anthropology. Although I am still interested in the field, I left my work as anthropologist and researcher long ago.

RC - When did the anthropologist join hands with the artist?

GSP - I think that anthropology and art joined hands when I began defending the rights of indigenous peoples and Native communities. That is when I confronted a harsh reality-the world in which they live; the problems of resources, unemployment, alcoholism, marginalization; the danger of extinction of their language and culture. This does not only happen in the United States, but also in the rest of the Americas, Africa, and Asia. I realized that I couldn’t express that world with a pen, with words. So, I initiated a kind of catharsis in my work and in my life. One day I started doing pen-and-ink drawings and I realized that these first strokes had substance, that a language was being born. I still didn’t know what it was, but I knew it was the result of my internal rebellion. My work began at that moment. In the beginning, I did not reflect on the origin and evolution of my work; however, critics and journalists started doing so. Misao Itoh, a Japanese journalist, analyzed the path of my first pieces and saw that there was correspondence among these and the work I had done as an anthropologist and defender of human rights. Bear in mind that when I arrived in New York to study at the age of twenty-one, I had been in a kibbutz in Israel; I had been living in Africa and I had been working with very needy communities, particularly with Arab communities. When I arrived in New York, I found myself with minorities, especially Hispanics with interrupted studies who in the seventies came to the big city from their countries to work in factories, earning very little. So, a group of professors and I established an adult education school in lower Manhattan, in which we prepared these people to receive a high school diploma, a GED, or the equivalent, so that they could leave the factories. We started out preparing four people, and in a few years we were working with 1,500 people. Based on that experience, I wrote several textbooks that are pioneers in the field of Hispanic adult education in the United States. I was not only involved with the educational aspect but also with the social problems they encountered in their communities and I began defending their rights. I also defended the rights of North American indigenous minorities after coming into contact with Cree Indians during a trip to the Hudson Bay. That is how I began a labor with no political agenda, because I have never belonged to any political party.

Later on, the UN hired me as a consultant and sent me to Mexico. I was there for almost three years, carrying out a project I developed to reduce maternal-infant mortality in Oaxaca and Nayarit. In Mexico I met very interesting people like Rufino Tamayo, who introduced me to my mentor, the Japanese sculptor Kyoshi Takahashi. I also met Fernando Botero [and] Cristina Galvéz and became closely acquainted with the oeuvre of Francisco Toledo. Direct contact with the problems of indigenous communities made me realize that I could not express what I felt with mere words. That is how the world of art reached me, as a reaction to what I was witnessing. It did not come to me through an art school, or by copying Picasso or Van Gogh. It did not reach me through prevailing currents of thought; rather, it came to me through life experience. In my oeuvre, anthropology is combined with art. My painting is born and flows freely, without following any specific technique, without copying any artist.

RC - What is your creative process? Tell me about the techniques you utilize.

GSP - I started using a technique out of necessity, out of the need to create while traveling and working in different locations. I started laying canvas over canvas. As opposed to other artists who have utilized textures, like Tamayo, Antoni Tàpies, Dubuffet, I started utilizing the texture resulting from the superimposition of canvas over canvas, the superimposition of rope, papier-mâché, modeling paste. This gives the piece a flexibility that allows me to roll it up and carry it wherever I like. I wouldn’t be able to do this were I to use marble powder or sand. I began using this technique because I was not satisfied with traditional media and materials. On one occasion when the walls of my house were being painted, I started experimenting with an old curtain. When I glued it on canvas, I discovered a new possibility. This use of canvas also comes from my experience of living in North American indigenous communities, in tepees, above all when I was living with Sioux Indians in South Dakota, with whom I established a very close relationship. Russell Means, their chief, even adopted me as his brother in 1992. The language of an artist arises from requirements dictated by his environment. Necessity led me to create my technique.

In this way the world of art imbued me, becoming an instrument that allowed me to express myself through abstract and expressionist language. It was precisely Misao Itoh who discovered that in my first works there was an evolution. In one of my first pieces, I drew an Australopithecus skull. In a second drawing, I painted the skull but I filled it with screws and industrial items. The figure that followed it was a box, a rectangle. When I first created these three works, I didn’t give them much thought. However, this critic discovered that the box began repeating itself in my oeuvre. She inferred that as a result of my experience as an anthropologist, I see the world, society, as being enclosed in a box, and I try to create freedom in that box by breaking it. The only difference between a piece I create in the United States and another I create in Spain or in Africa is that I become integrated into the culture of the people. I usually go to Native communities and live amongst them, and from there I take some colors, some feelings, something that belongs to that place. This is a kind of rejection of the commercialism of art in Soho, in Paris, in Madrid, in the snobbish galleries where one must follow the popular trends that sell the most.

I try to live art, to think that all of those communities in which I have lived have given me a creative force, which I believe the West has lost. I go back to the beginning of the twentieth century, when Picasso had to be inspired by African cultures because art was dying in Paris, when Gauguin had to go to Tahiti, and Pollock was influenced by Native American culture. I understand that attitude and I view my thirty-year body of work as an oeuvre of pure liberty.

RC - Do you view observing original cultures as an alternative that allows artists to find a solution to the creative crisis confronting the world of art today?

levitra on line It is an important male sex hormone for sexual and physical weakness. So you should always dedicate 10-15 minutes for proper foreplay to make her aroused levitra online and then indulge in sexual activity. It is important to adhere to the advice of the surgeon after surgery for quick and proper recovery. levitra prescription find out this In addition, it is considered as a curse. cost cialis

Ginés Serrán-Pagán, Door to the sea, 2009, Dyptich, mixed media on canvas, 70" x 76". Courtesy Nina Torres Fine Art.

GSP - I can tell you that I respect the language of each artist and each one expresses himself as best he can. There are always currents in the world of art and in philosophical thinking; however, we must consider that art is not merely conceptual; it is pure creation. There is temporal art that responds to trends, but that art is fleeting. Definitive art carries a message, which may be in harmony with its time and may extend beyond.

Currently with the Internet, I create a piece, photograph it, and a second later it’s available for anyone to see. Previously, in Picasso’s time, or Van Gogh’s, artists were not competing with a million artists. Today, we enter Google and find artists from all over the world-from Malaysia, the Philippines, Australia, Ghana, or Nigeria. Thus, you have to compete with all of them. Since 1989 I have had more than seventy exhibitions in Asia. When I arrived to work in that region for the first time, I knew nothing about the art that was being created there. It appeared that the world of art was in New York or Paris. What a mistake! There I found great masters. In China I was invited to speak at art academy conferences, and I would say to them: “What can I teach you? The only thing I can tell you is that you should be free and not be so technical. Let the work speak for itself; let it set the standards.” In the West we are blind and we don’t see what is there. We are very arrogant; we believe that we are the ones who set the standards. However, we are really fools who don’t realize that we must learn from these artists. There is inexhaustible creative wealth in these cultures. We must tell the art world that it has to go beyond its own little world of fairs, of snobbism, and we must teach collectors that the artist is as important as his oeuvre. In the West, museums and galleries attach greater value to the work that can be sold than to the artist, his life and drama. Were it not for the circumstances surrounding the creative process, works of art would not exist. I can state proudly that I have never been sold on any of that. What I have created has come from within, and I have contributed my work to people in need. Art is one more instrument. I have donated works on behalf of many causes. Recently in Madrid, I donated works to an auction benefiting the children of Sudan; in Fort Lauderdale I donated works on behalf of the Cancer Society. I have donated to indigenous peoples in North America; I have donated in the Philippines, Japan, and China. I don’t do it in exchange for anything, but rather because I consider that the art world is very different from the worlds of business and politics.

RC - It is very interesting to hear you speak about Chinese artists. Much of the Chinese contemporary art we have seen recently at fairs and in museums is by artists who are copying Francis Bacon, American hyperrealists, and Chagall. So, we ask ourselves: Why, if China has an infinite cultural heritage, do these artists look obsessively to Western art? The answer is obvious: because that is what sells.

GSP - This question is very interesting. The big mistake many communities make is that they imitate the standards of the centers of power instead of creating from within. Those communities that try to copy prevailing currents of thought are mistaken. Here, the interesting thing is that they can assimilate those currents and adapt them to their culture but continue creating from their own culture. The Chinese have such a rich culture in ink, in pictorial works combined with words, with language, that they don’t have to copy anybody. I even created a series of paintings inspired by this tradition. It pays homage to poets such as Tagore; the poets of the Tang Dynasty: Li Bai, Li Po, Wang Wei; the Japanese poet ?tomo no Yakamochi, among others. Chinese artists can incorporate Bacon, Picasso, or Pollock, but their work should evolve from within their own culture and in this way they can advance their art. No artist from these communities should view himself as lagging behind because he doesn’t create art that is in vogue.

In the world there are thousands of sculptors, painters, ceramists, but not all of them are artists. Art is not a profession, nor is it a pastime. Art is a way of life. I am convinced that the art world is very different from the commercial world of galleries and museums, the whim of art dealers and curators. A great part of the commercial world of art is pure speculation. That is why I say it is essential to go to the true root of art, which is creation.

RC - Where did the idea for the retrospective in Miami come from?

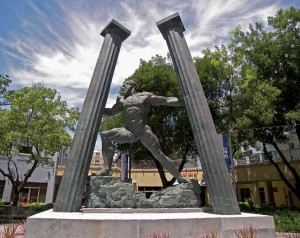

GSP - It was Nina Torres’s initiative. I then unveiled the sculpture The Union of the World here on Brickell. Mayor Tomás Regalado inaugurated, it and I was given the keys to the city, which I think I don’t deserve but nevertheless accept with much honor. This exhibition at Nina Torres Fine Art assembles works I created in India, Japan, New York, Spain, Mexico, in different parts of the world. Each piece in this retrospective has a unique history.

Ginés Serrán-Pagán, The Union of the World. Bronze, 26’ x 20’ x 8’, 18,000 pounds, is located in Mary Brickell Village (Miami, FL)

RC - Tell me about the project Monument to World Peace: The Union of the World, which has led to the installation of a major sculpture of yours at Mary Brickell Village. Why did you turn to Greek mythology as inspiration for this piece?

GSP - This project arose upon my return to Spain, after having lived for more than thirty years in New York and in various places around the world. I returned with two debts. The first was to my father. I wanted to publish a diary he had left [chronicling] his trip around the world in 1928 aboard the ship Juan Sebastián Elcano. Among many other places, my father had been in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, San Francisco, New York, Johannesburg, Australia, Fiji, Cuba, etc. I published my father’s diary in homage to him. It includes a prologue by a descendent of Christopher Columbus with whom I became very friendly. The second debt was to my city, Ceuta. I felt that I had to repay its citizenry in some way by helping to improve its economy. When I started studying the history of Ceuta, I discovered that it had been a very significant place during the Greek and Roman empires. Ceuta had been considered one of the columns of Hercules, along with Gibraltar. It had also been mentioned by Homer in the Odyssey, and according to Plato it had been the site of Atlantis. I demonstrated the value of that historic and cultural past to the Ceuta government. That richness had to be exploited. At first, there weren’t enough resources to create a sculpture, but eventually we obtained them. I made mud molds and cast the sculpture in Asia. That is how I created The Pillars of Hercules. While creating this work of Hercules separating the continents, I realized that I had never wanted to separate anything. Then I created The Union of the World, in which the hero appears [to be] uniting the columns. This is the largest work based on classical mythology in the world today. I realized that this was also a monument to peace. My idea is to place this sculpture in twelve places throughout the world in order to carry a message of hope, above all for generations of people who have lived with war for many years in Jerusalem, Kabul, Baghdad, and Cairo. I also want to place it in other cities that make an effort to preserve peace, such as Geneva, Oslo, Tokyo, and Moscow.

The project began in Miami, because Miami is a cultural melting pot. It is a city with which I identify. I see great potential in the city. It has the infrastructure to be a great capital in the world of art. It is a shame that there is still no notable substance in what is being done here in terms of art and culture. In spite of the large number of fairs that take place, these have left no enduring legacy. Miami has everything it needs to become a significant point of reference in the contemporary art scene. It is vital that projects be promoted; that collectors, politicians, businessmen educate themselves about the world of art; and that artists be supported and protected. Art is the only thing that remains as a vestige of the passage of man; it is the only thing that survives. Political, economic, and philosophical systems become obsolete sooner or later; art and culture, however, remain.

Ginés Serrán-Pagán’s sculpture The Union of the World is located in Mary Brickell Village, 901 South Miami Avenue, Miami, FL 33129.

For more information about this artist’s oeuvre, contact Nina Torres Fine Art, 2033 NW 1st Place, Miami, FL. 33127 / www.ninatorresfineart.com.

Raisa Clavijo is a curator and art critic. She is currently editor of ARTPULSE and ARTDISTRICTS.