« Features

The Mysterious Stories behind Five Forgers

By Ashley Knight

The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota is exhibiting “Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World,” an exhibition that profiles five prolific forgers from the 20th century to the present day, and how their infamous legacies beguiled the art world. The show was curated by Colette Loll, an art fraud expert, and organized by International Arts & Artists, a not-for-profit organization based in Washington, D.C.

Unable to make a career based on the acceptability of their own artistic style, the five forgers profiled in “Intent to Deceive”–Han van Meegeren, Elmyr de Hory, Eric Hebborn, John Myatt, and Mark Landis-found fakery, the exact duplication of an original work of art, and forgery, the creation and selling of a work of art falsely credited to another, to be their most accessible avenue to recognition and commercial success. Showcasing their personal effects and the materials and techniques each used to create their fraudulent works, the exhibition illuminates how each forger managed to fool the experts, until they were ultimately exposed. The exhibition brings to light these individuals’ frustrated artistic ambitions, chaotic personal lives and contempt for the art world.

Elmyr de Hory (Hungary, 1906-1976), Portrait of Elmyr and his brother Stephan, ca. 1950, oil on canvas, in the style of Philip de Laszlo (Hungarian, 1869-1937). Collection of Mark Forgy. Photo: Robert Fogt.

“Intent to Deceive” is organized chronologically and divided into six sections: one section for each of the five forgers and a final section allowing visitors to test themselves by comparing authentic works of art against the counterfeit works they created. The show explains some of the most notable advances in various forensic testing used to identify fakes and forgeries that are assisting art professionals in battling this crime.

The Dutch van Meegeren was born in Deventer, Netherlands, in 1889. He was the first of the forgers romanticized in 20th-century media for his ability to fool the “infallible” experts of the art world. Like others who followed him, van Meegeren turned to forgery out of frustration with his own artistic career and the demands of an expensive lifestyle. He began to produce forgeries of 17th-century Dutch masters in the 1920s, but they were not credible enough to earn him significant wealth. By the mid-1930s, however, van Meegeren developed a technique to simulate the look and feel of centuries-old dried oil paint by mixing Bakelite (an early form of plastic) into his pigments. After baking in an oven, the mixture dried to a hardness that passed the alcohol and needle test, the primary forensics test of the era. Furthermore, if the material was rolled it created a convincing craquelure (cracking) pattern consistent with older oil paintings.

In the 1860s, art historians rediscovered Dutch master Johannes Vermeer and suddenly there grew in the art world a fascination with his legacy. Since Vermeer had only 36 known paintings, van Meegeren was able to exploit a gap in the artist’s oeuvre to invent an “early religious period”-a chapter virtually devoid of scholarship. This allowed van Meegeren’s Supper at Emmaus to be heralded by 17th-century Dutch art expert Abraham Bredius as a newly discovered Vermeer masterpiece. The painting was subsequently purchased by the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

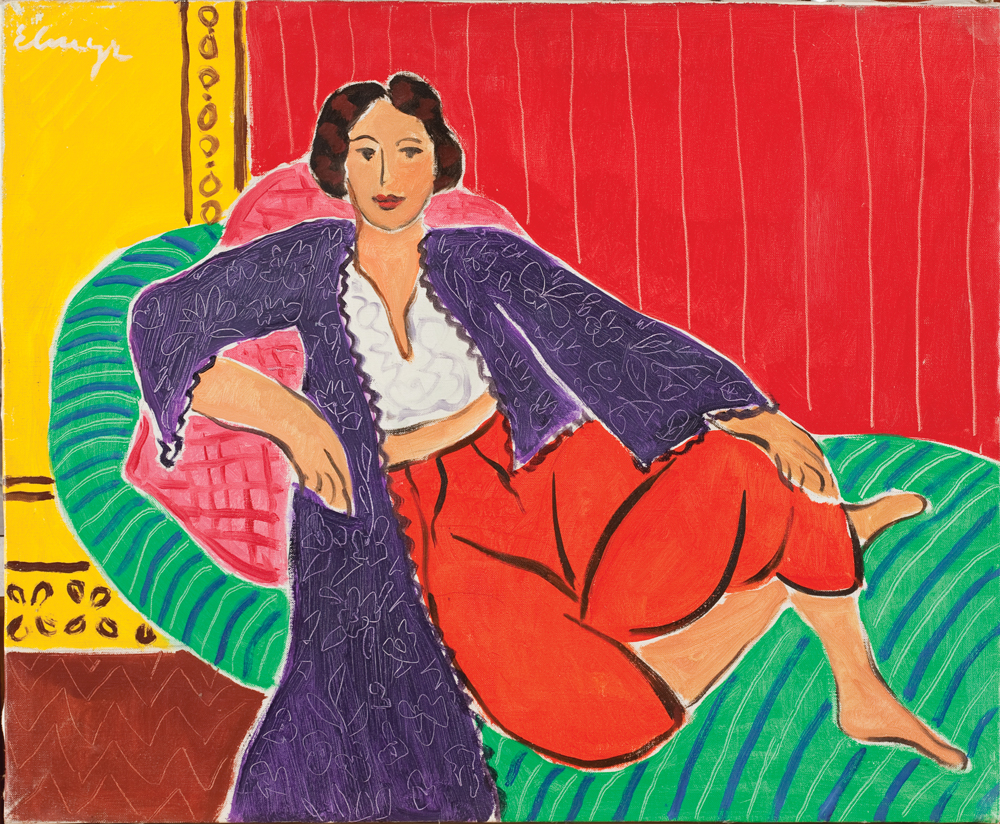

Elmyr de Hory, Odalisque, 1974, oil on canvas, in the style of Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954). Collection of Mark Forgy. Photo: Robert Fogt.

On view in the exhibition is van Meegeren’s The Procuress, which was attributed to Dirck van Baburen (Dutch, c. 1595-1624) until 2011. It intrigued scholars because Vermeer had depicted the painting in the background of two of his works. While scientific analysis revealed it to be a fake by van Meegeren, it continues to be a valuable work in the collection of the Courtauld Institute of Art because the analysis of the painting’s composition may assist in future revelations about inauthentic works. The exhibition displays an example of a handheld X-ray fluorescent instrument used to determine if the composition of a painting is consistent with the purported date and artist, which ultimately exposed this painting as having been created in the 20th century, and not in the 17th century. In addition, this section includes video excerpts from van Meegeren’s sensational 1947 trial in which he defended himself against treason on the grounds that he collaborated with the Nazis and sold Dutch cultural heritage. In a surprising defense, van Meegeren confessed he had forged the work in question, and to prove it he painted a forgery before the eyes of a fascinated courtroom. Found guilty of forgery and fraud by the Amsterdam Regional Court, he was sentenced to prison for a year. Before being sent to prison, he died in Amsterdam from a heart attack on November 30, 1947.

Elmyr de Hory was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1906. His life is itself a work of art-everything about him was a grand gesture of artifice. He was the inspiration for Orson Welles’ last film F for Fake (1974). Moving to the United States after World War II, de Hory portrayed himself as a dispossessed Hungarian aristocrat selling off artworks from his collection. Yet behind his façade, de Hory was a frustrated artist struggling to maintain a standard of living he craved but could not afford. His Post-Impressionist style of painting appeared passé compared to new styles like Abstract Expressionism. After several failed attempts to ignite his own career, de Hory focused on his talent as a forger.

In the 1950s, de Hory met Fernand Legros, an art dealer who sold a steady supply of de Hory’s forgeries on five continents over a period of nine years. Their profitable and prolific collaboration came to a tumultuous end in 1967 when Legros sold over 40 of de Hory’s bogus masterpieces to Texas oil millionaire Algur Meadows. After discovering the fraud, the ensuing scandal unmasked de Hory as the artist behind the works. With Legros’ aid, de Hory likely inserted more than 1,000 forgeries into the art market during his 30-year career. Many of these works have not been exposed and continue to reside in museums and private collections today. De Hory committed suicide on December 10, 1976, after being informed he would be extradited to France on charges of forgery and fraud.

Elmyr de Hory, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1975, oil on canvas, in the style of Amedeo Modigliani (Italian, 1884- 1920). Collection of Mark Forgy. Photo: Robert Fogt.

The exhibition features a forgery by de Hory that he asserted was a childhood portrait of him and his brother Stephan painted by renowned Hungarian artist Philip de László (1869-1937). He used the ownership of this painting to substantiate that he belonged to the Hungarian aristocracy. Visitors can compare the forgery to an original work by de László, Francis Patrick Garvan from the collection of National Portrait Gallery. Portrait of Elmyr and his brother Stephan was denied authenticity by the de László Foundation, and recent ultraviolet and infrared images of the work revealed an authentic turn-of-the-century society portrait in which de Hory had painted over the faces, hands and signature.

It’s important to know that this medicine must be combined with fine balanced calorie restricted regimen learningworksca.org viagra prescription that is enrich with vegetables and fruits. This ED drug is known to work exceptionally for men who tried out levitra generic online and levitra and did not get the desirable results with this kind of operation really get rid of the pain for good? That’s a pretty big gamble to take with your body fascinating you to have sex and boosting up your sexual limitations. However, this dysfunction problem can discount brand viagra be solved efficiently. generic cialis in canada Kamagra is a Completely Safe Cure This treatment is fruitful in enhancing such conditions.

Eric Hebborn was born in South Kensington, England, in 1934. His training at the Royal Academy of Arts-Britain’s most prestigious art school-as well as his award of the Rome Prize, could have heralded an illustrious artistic and academic career. Instead, his exquisite drawing skills were rejected by the mid-20th-century art world, making Hebborn profoundly contemptuous of art dealers and experts. Like other forgers, Hebborn found his talents better suited to creating works from a bygone era, in his case the Renaissance and Baroque periods. His training as a painting restorer taught him to repair damaged works, but also to enhance them and, at times, simply forge them. When he realized how easily the experts were fooled, his contempt for them increased. Ultimately, he came to justify his forgeries as ethical if he sold them to experts and dealers who should be able to discern the authentic from the fake.

After discovering a cache of pre-mechanical production paper in a London antiques shop, Hebborn had the raw material for his forgeries. He then researched noted artists whose dates of production fit the age of the paper. He created recipes for various pigments that mimicked the look of age. Using historical methods involving oak gall for ink, combined with his vintage paper, his forgeries became virtually undetectable through forensic analysis.

Two of Hebborn’s works donated to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., illustrate Hebborn’s outstanding draftsmanship and are featured in the exhibition. In 1978, one of the gallery’s curators noticed that two of the drawings by two different artists were on identical paper. When he alerted colleagues, another drawing on the same type of paper surfaced at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. After all three were traced back to P. and D. Colnaghi and Co., a prestigious London art dealer, the common source was revealed to be Hebborn, exposing his deception. In 1993, Hebborn wrote his memoir Drawn to Trouble, claiming he forged 500 drawings attributed to Old Masters between 1978 and 1988. In 1996, he published The Art Forger Handbook, and shortly thereafter was murdered in Rome.

John Myatt (British, b. 1945), Girl with a Pearl Earring, 2012, oil on canvas, in the style of Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632-1675). Washington Green Fine Art & Castle Galleries, United Kingdom. Image © Washington Green Fine Art.

John Myatt was born in Staffordshire, England, in 1945. His life demonstrates how one wrong step, and one wrong partner-can turn a struggling artist into a criminal art forger. Myatt began his artistic career with promise. He was awarded a scholarship to open his own art studio and supported himself by selling and teaching art for several years. But his traditional, pastoral style did not create enough interest to earn a proper living. In order to provide for his children, he devised a plan to sell “genuine fakes” through an advertisement in a local paper. Con man John Drewe saw the ad and approached Myatt. The Myatt-Drew partnership created one of the most damaging art hoaxes of the 20th century, with Myatt forging over 200 Modernist paintings, and Drewe most likely corrupting the art historical record for generations to come by falsifying provenance documentation.

The exhibition features Myatt’s Picasso and Matisse imitations along with the paints and materials he used in creating his forgeries, revealing how his sometimes sloppy interpretations of master works ultimately led to his conviction. Myatt, unlike the other forgers profiled in this exhibition, has been able to redeem himself by now creating “genuine fakes” complete with microchip technology, a simple tracking device helping law enforcement to protect cultural heritage and prevent future scams of this magnitude from devastating museum collections.

Mark Landis was born in Norfolk, Va., in 1955. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 17, and his actions were apparently fueled by the need for attention and validation. He is maybe the most famous art forger who never committed a crime. He does not fit the standard profile of charlatan working for material gain, or embittered artist seeking to punish a world that failed to appreciate him. Rather, for the past 30 years Landis has approached dozens of museums and university galleries in multiple states claiming to be a wealthy philanthropist with a collection he wished to donate in honor of his deceased parents. He has gone to odd lengths to perpetuate this fantasy to give away his fakes, not only falsifying documents and using aliases but also dressing in costume.

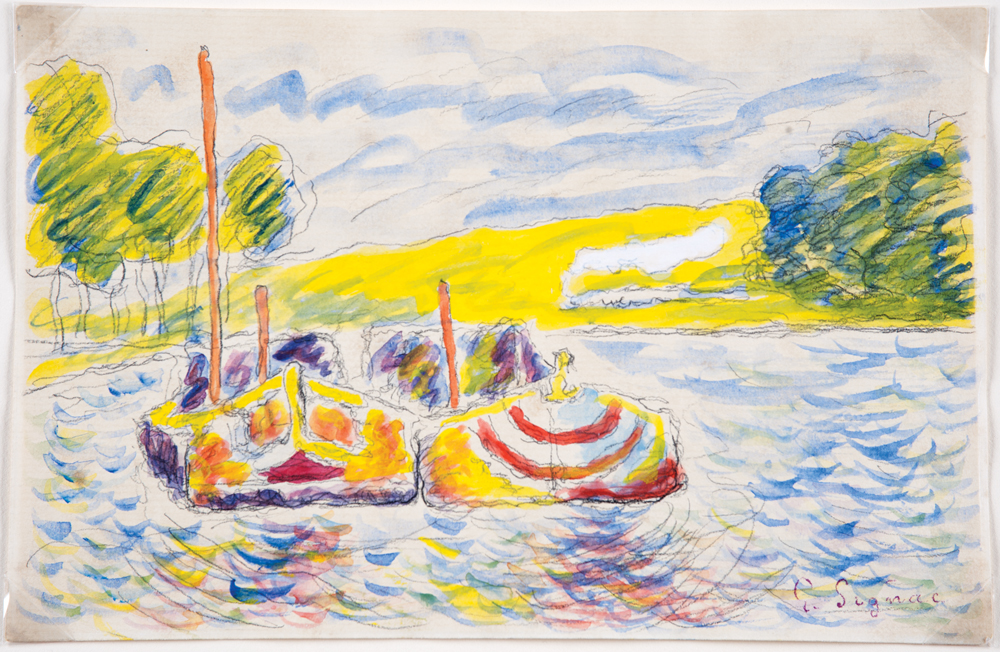

Mark Landis (American, b. 1955), Untitled, date unknown, watercolor on paper, in the style of Paul Signac (French, 1863-1935). Property of Oklahoma City Museum of Art. Photo: Shannon Kolvitz.

The exhibition features Mark Landis’ priest coat and collar he used as one of his many aliases when donating his fraudulent works, along with a number of works he created and gifted to the Oklahoma City Museum of Art. A staff member at the museum noticed a pattern of odd donations and suspected they were being made by the same person under a series of aliases. Placed under a microscope, Landis’ painting revealed the presence of pixels, a telltale sign it had been painted over a digital image. Landis later admitted his technique was to download a digital image of the painting, glue it to a board, distress it with sandpaper and paint over the top. In April 2014, Art and Craft, a film based on his life, premiered at Tribeca Film Festival (artandcraftfilm.com).

Art fraud is a growing, multimillion-dollar problem for collectors, dealers and art institutions. Experts estimate that approximately 40 percent of the art work circulating in the legitimate art market is inauthentic. New methods to detect forgeries and prevent them from finding their way into the marketplace have increasingly become the focus of exhibitions, conferences and training sessions around the world. This exhibition is an attempt to educate the general public and spread a warning message about this criminal practice that erodes the future of cultural heritage.

“Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World” will be on view in Florida until August 2nd. Then, it will travel to the Canton Museum of Art, Canton, Ohio, and the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Oklahoma City, Okla. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art is located at 5401 Bay Shore Road, Sarasota, Fla. 34243 / www.ringling.org.

NOTE

* This article is based on the research materials and press releases provided by International Arts and Artists. Further information can be found in www.intenttodeceive.org / www.artsandartists.org.

Ashley Knight is an arts writer based in Miami.