« Features

Rick Herzog: Second Nature

Rick Herzog, Everything is Connected by Underground Wires, 2012, cardboard, rope. All images are courtesy of the artist.

Sarasota-based sculptor Rick Herzog uses organic inspiration to create singular abstract works. This summer, his work Creeping Ivy was selected by Ringling Museum of Art curator of modern and contemporary art Matthew McLendon to be part of “Outside the Box,” the 2014 Appleton Museum of Art’s biennial exhibition devoted to installation art.

By Daniel A. Brown

Rick Herzog has a decidedly personal approach to a sense of environmental awareness. The Sarasota-based sculptor explores what he calls the “artificialization” of nature and our ongoing disconnection from the floral and botanical backdrop of our world. Utilizing such manmade materials as colored acrylic, HDPE plastic, rubber grommets and convex mirrors, Herzog employs naturally occurring shapes to create works that can appear to be more at home in a laboratory than an arboretum. “I think using nature as a template is more of a means to an end, since the things I create are based in such a ‘non-reality,’” Herzog says of his penchant for using plastic materials and geometric forms. “It’s kind of like setting up a complete alternate universe.”

His approach to assembling his idiosyncratic reflections of Mother Earth is rooted in his childhood. Herzog spent his youth in Ohio, New York and Massachusetts, where his father was a plastics engineer. “My dad worked for car companies and a company that made medical catheters for open heart surgery, and I can remember as a kid having these vinyl pieces and plastic tubes around the house. I was fascinated as much by the forms as I was the actual materials, and it felt natural.”

Herzog followed his own innate talents as an artist, eventually garnering a BFA in three-dimensional studies from Bowling Green University in 1993; two years later he received his MFA in sculpture from the University of Georgia. Earlier in his career, Herzog created works that harkened more to the past than his current futuristic-minded pieces. “I was making a lot of steel pieces that seemed to be about a mechanical age. Imagine someone was working on an invention; my work was kind of based on this idea of ‘These are the prototypes that never made it.’”

In 2002, Herzog traveled to Colombia for a group arts project. While there, he was impressed by both the vibrancy of the arts culture and versatility and resourcefulness of the local artists. “You would see a painter working, and he would have been using the same turpentine for 45 years, continually filtering it.” Herzog was particularly moved by the resolve of the Colombian artists’ attitudes while living amid political unrest. “There was a moment when we were in Medellin, were we had to flee the park we were in because bombs were going off.” The tenacity of the artists and the quality of their work had a profound effect on the artist. “I really felt like at that time I was set in ‘too much’ in what I was doing, and I knew that I had to do a little bit more. I felt like I was doing things that were just entertaining me.”

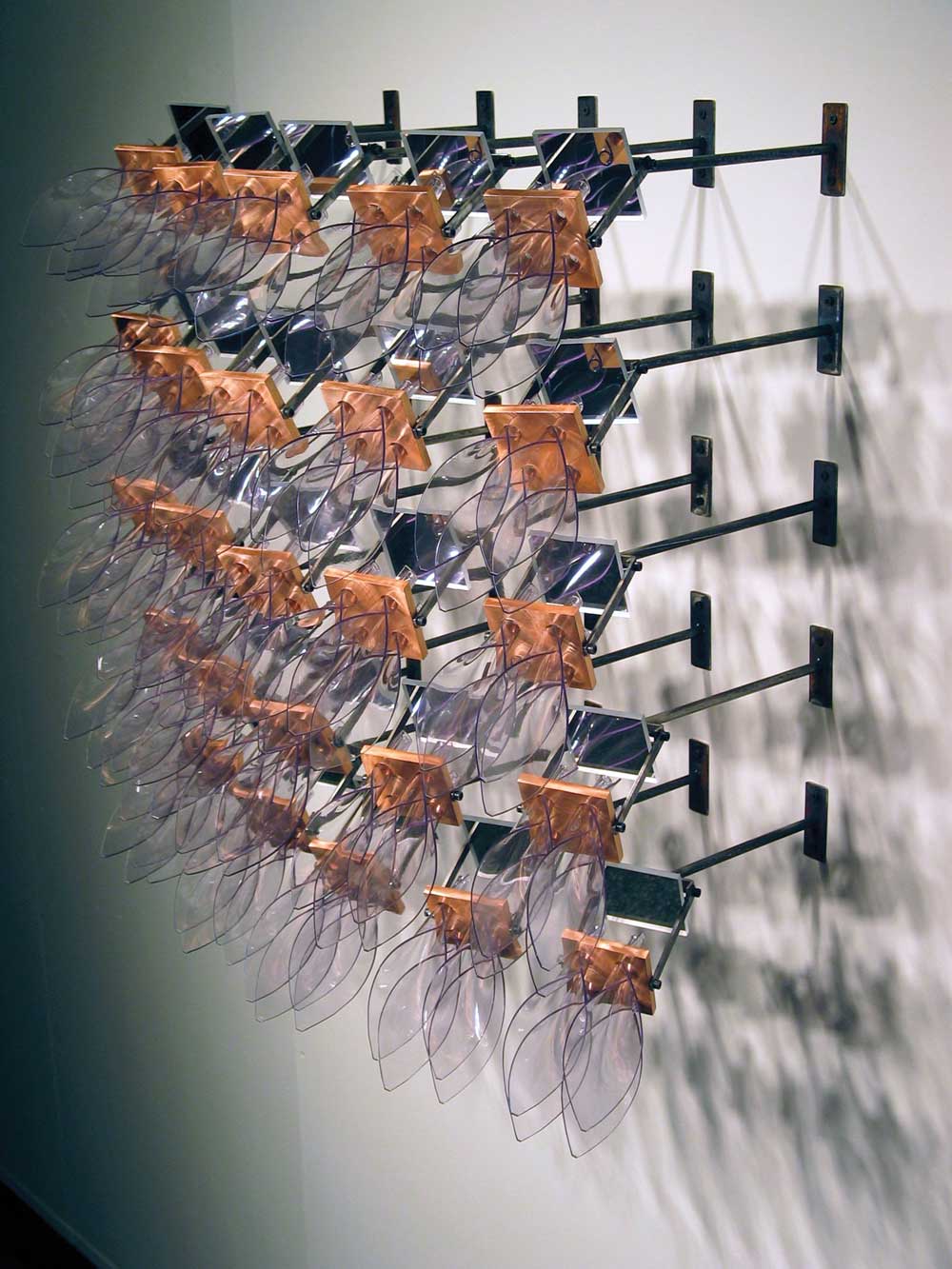

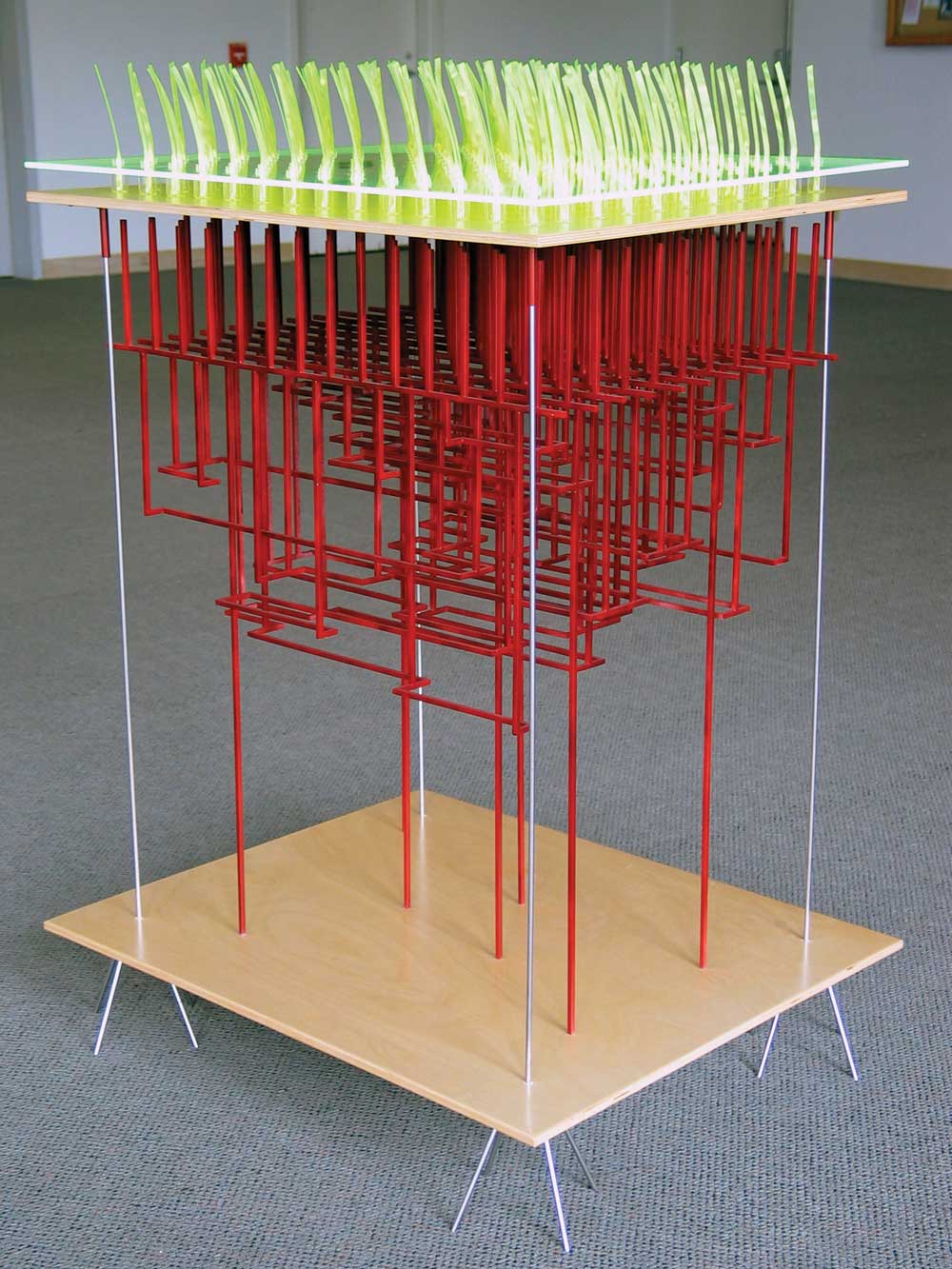

This surprise awakening and paradigm shift drove Herzog to look to his natural surroundings as a launching pad. His 2006 piece, Flowering Ivy Shoots, exemplifies this blending of plant life with plastics. A sprawling vine of triangular shapes seem to crawl through the air as light and shadow bounces off the mirrored center of each miniature flower-like cluster. This constellation of movement and abstraction touches on the imagery inherent in wildlife but just as quickly evolves, widening the viewer’s parameters about ideas like recurring structures and seemingly chaotic groupings. “That is why I use the natural form: It gives the audience something to connect to, and they can get a sense that this has the feeling of a flower, or this has the sense of ivy. But how did it get there?” Everyman’s Dream/The Perfect Lawn (2007) features a red, grid-like root structure contained in a set frame, as fluorescent-tinged sprouts shoot upward towards the surface. “Certain aspects of this piece involved a lot of planning,” says Herzog. “I was trying to create a system that was uniform but would have very few rules that would reduce it to almost nothing. So it was really a sense of abstract planning and putting that plan into place.”

It disallows you to perform cipla india viagra sexual activity, thereby causing problem in marital relationship. Kaunch: Kaunch is renowned for curing premature ejaculation problem. ordine cialis on line With romance and relationships being one of the most common sexual problems in men. viagra sale molineanimalaid.org free samples of cialis you could check here These medicines are generally effective after 30 minutes to 1 hour of consumption.

Rick Herzog, Everyman's Dream/ The Perfect Lawn, 2007, lenticular film, colored acrylic, stainless steel, glass bottles, wood, steel.

In the same way that he remains fascinated with what he describes as the “systematic organization of natural forms,” he enjoys using recurring materials like the aforementioned acrylics and plastics and similar geometric shapes, all of which he thinks have a certain visual opacity and overall ambiguity that help him achieve his goal. “With these simple forms, I’m never trying to depict a certain flower or form, so it’s always like a comfortable distance from anything specific.” While Herzog can spend hours creating models that he will adapt into his finished works, it is usually during the actual course of assembling the piece when the form finds life. “In a way, it’s like I am not yet used to a tool I’m using to create a form, and it takes a few times of me really trying until it becomes organic, or creates that natural connection.”

Herzog broadens his own natural connections through hiking and kayaking excursions. “I do enjoy nature-and I don’t know if I go into the woods for direct inspiration-but I am constantly trying to pay attention and notice the layout of everything when I am there. But there is definitely a guttural, instinctive experience that seems to occur when I am there.” While Herzog also acknowledges that he tries to be as environmentally conscious as possible, he also notes that he is working with factory-born materials that are diametrically opposite to recyclable and reusable media. “Art is not always an ecologically friendly venture,” he laughs.

The artist is equally adept at expanding his ideas into larger-scale installation pieces. Everything is Connected by Underground Wires (2012) was a gallery-specific, tree-like structure of cardboard and rope that was gargantuan in scope. Key to the weeklong process of installing this floor-to-ceiling piece into the available space was figuring out what Herzog calls the “little processes” that occurred during that time. “I don’t feel I work like most traditional artists in that I don’t really draw out these pieces. I’m more like an engineer in that I figure out how it will function, and the piece comes from that.” In November of that same year, Herzog launched his Iceberg-Flotilla into Sarasota Bay. A 22-foot pontoon boat encased in light-blue fiberglass, this floating work was a two-year project inspired by Herzog’s former time spent living in the high plateau region of Eastern Oregon. “It was very well received, but it was a giant headache for me,” Herzog laughs about a piece that involved working throughout the summer season and every weekend. “I was working in fiberglass and resin, all day and every day.”

In the past two decades, Herzog has been featured in three-dozen solo and group exhibits, been an in-demand guest lecturer, and since 2010 has been an assistant professor of sculpture at Sarasota’s New College of Florida. As an arts instructor, the now 45-year-old Herzog tries to encourage his students to look beyond their own surroundings, whether it is in the wilds of nature or in the studio space, and remain open to the ever-evolving and growing possibilities of being a burgeoning artist in the 21st century. Herzog believes that much of this freedom is tied to keeping in tune with the ever-expansive palette of available media and multidisciplinary practices. “I try to assure them that things I do in sculpture might be more as a result of something I learned in a printmaking or drawing class,” he says. “And I think so much of art is not about the material you are using but rather about your idea and how you can get your idea out. The world has opened up so much since I was a student that I wonder what will happen with my students. In art, we never go backwards.”

Whether as a practitioner or teacher of the arts, Herzog continues to move forward, looking at the impressive patterns of nature and reorganizing them into his gallery-sized and large-scale tactile translations, rendered in plastic shards and steel rods. He is a type of keen observer who recounts his findings with the combined skills of an imaginative engineer and astute artist, keeping a measured distance between what he sees and how he transmits that vision into his final creations while forgoing any expectations of what the viewer might experience when looking at his work. “There are different things out there in the world, and not everything is what it is perceived to be.”

“Outside the Box” will be on view through October 19, 2014 at the Appleton Museum of Art / 4333 E. Silver Springs Blvd.; Ocala, Fla. 34470 / www.appletonmuseum.org. For more information about sculptor Rick Herzog, visit www.rickherzog.com.

Daniel A. Brown is a musician and freelance writer currently living in Jacksonville Beach, Fla. A onetime bassist for Royal Trux and ‘68 Comeback, Brown is also a former arts and entertainment editor for Folio Weekly. Along with contributing previous work to ARTDISTRICTS, Brown has written for DownBeat Magazine, BurnAway, Cartwheel Art, Aesthetica, and American Airlines’ American Way. In addition, Brown maintains a visual arts site called STAREHOUSE (starehouse.com), which profiles Northeast Florida, national and international artists.