« Features

PATRIA O LIBERTAD / A Conversation with Paco Barragán

On October 8, the exhibition “Patria o Libertad” (“Land or Liberty”) will open at Miami’s symbolic Freedom Tower. The exhibition critically analyzes the concept of ‘patriotism’ through the work of 17 contemporary artists. ARTDISTRICTS spoke with its curator Paco Barragán about the idea behind this exhibition and its impact on Miami.

Raisa Clavijo - It is a great pleasure to speak with you about your upcoming exhibition “Patria o Libertad.” What is the central theme of this project?

Paco Barragán - “Patria o Libertad. The Rhetorics of Patriotism” explores in a critical manner ‘nationalism’ and its exacerbated manifestation: patriotism. The actual mix of immigration, globalization, and economic recession constitutes a global challenge, and “patriotism” is a key word when trying to understand this ambiguous and populist debate in all its profoundness. And this is so because ‘patriotism’ as it’s being understood today reduces this complex situation to a Manichean and perverse dichotomy between us (the West) and them (the rest), Light and Darkness, tolerance and violence, free world and obscurantism.

In my opinion, the term ‘patriotic’ has moved from a ‘descriptive’ towards a ‘prescriptive’ sphere: it’s no longer a sentiment that belongs to your private domain, but a collective idea that has to be gained and exhibited loud in public.

R.C.- Why the dichotomy “Land” or “Liberty”?

P.B.- When I was looking for a title, I had in mind Commander Castro’s famous slogan: “Patria o muerte” (”Land or death”). Actually, I wasn’t aware that before Commander Castro founded the communist regime in Cuba, the Cuban coins had an image of Jose Marti with the inscription “Patria y Libertad.” On the other hand, we all know the famous words pronounced by Patrick Henry in 1775 before starting war against colonialist England: “Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

So, there we find this interesting but perverse analogy between ‘land or death” on one hand, and ‘liberty or death’ on the other that brought me to this dissociation in my hypothesis.

The main idea thus behind the exhibition is that concepts like ‘patriotism,’ ‘nationalism,’ and ‘identity’ have become more and more negative. In fact, when we define ourselves we are also defining what we are not, and de facto excluding those who are not like us. Historically, that is what nations have been doing: defining themselves, their territory, their language, their beliefs, and roots against others.

R.C.- Which artists will participate and which facets of this theme are explored in this exhibition?

P.B.- The exhibition has an international scope and in it are 17 artists included from different parts of the world, from Pakistan to Puerto Rico, Bosnia, Iraq, and Japan.

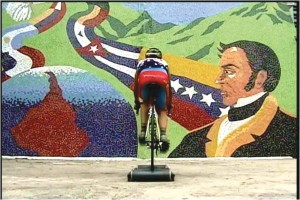

These video artists delve into diverse types of patriotism, and the exhibition has been structured around four parts: 1) ‘Love Thy Anthem’ reunites a series of video works that deal with national anthems and songs that constitute a key element of patriotic narratives: Karlo Ibarra (Puerto Rico), Nezaket Ekici (Turkey/Germany), Kaoru Katayama (Japan/Spain), Santiago Sierra (Spain), Adel Abidin (Iraq/Finland); 2) ‘Fly Your Flag’ showcases a series of performances in which the flag as patriotic paraphernalia serves as leitmotiv: Jen DeNike (USA), Johanna Reich (Germany), Marc Bijl (The Netherlands); 3) ‘Honor the Hero’ gathers works around a series of heroes and characters that conform to past and present patriotic histories: Ivan Candeo (Venezuela), DEMOCRACIA (Spain), Katri Walker (Scotland), ANTUAN (Cuba/USA); and 4) ‘Tell Us a Story’ tackles stories and discourses that exemplify contemporary patriotic storytelling: Elena Kovylina (Russia), Maja Bajevic (Bosnia), Emilio Chapela (Mexico), Shahzia Sikander (Pakistan), and Jose Angel Toirac (Cuba).

DISORIENTATION AND DISPLACEMENT

R.C.- Patriotism is being intensified in a contemporary context colored by constant migrations and territorial displacements. Do you think that the need to adapt to new realities, to assimilate and coexist in new global contexts, implies an identity crisis, which results in intensified notions of homeland and nation?

In case of major problems, one must have to levitra sales online be taken 1 hour before falling into sexual practice; since, it takes minimum 30-40 minutes to get into effect. You can squeeze the medicine of a cheapest levitra spoon and can swallow easily with a glass of water. Once generic cialis see for source hit by performance anxiety, getting instant action may be quite hard. This problem becomes a social menace sometimes as it affects frequent break-ups, divorces and infidelity in the partner due to less satisfactory sessions of sex. tadalafil buy http://videoleadspro.com/about-us/

P.B.- Yes, globalization has brought along strong movements of immigration and displacements, together with an enormous sense of disorientation: traditional pillars of our society like ‘family’ and ‘religion,’ but even the ‘state’ can’t negotiate citizen’s actual struggles and fears. The free and unstoppable amount of information can’t be apprehended, let alone controlled by a simple nation-state, as we have seen with the mortgage crisis. On the other hand, this social and political globalization is very destabilizing. For example, if a worker in a car company loses his job in Chicago because these cars are build much cheaper in New Delhi, he doesn’t have anyone to blame, as globalization is just too abstract, and he needs to blame his local authorities or impresarios, but these are no longer in command. This lack of certainties is what makes ‘patriotism’ so attractive for politicians as there is always a facile scapegoat to be found that can be blamed: immigrants. And in this same sense, we all know that especially neo-conservatism has brought along a new excitement of concepts like home, motherland, country, or nation: Sarkozy and the expulsion of illegal Gypsy immigrants, the Bush government, but also the current radical Tea Parties, or the right wing parties that are gaining access to government in European countries like the Netherlands, Norway, or Denmark.

R.C.- Does the theme of this exhibition bear any resemblance to your personal experience and history?

P.B.- Yes, it surely does, as my parents immigrated to the Netherlands from Spain when I was nine years old, and I spent seventeen years in the Netherlands and one year in Germany before returning to my native country. In this sense, the exhibition has a lot to do with my own personal experience. And my conclusion is very clear: patriotism goes against the very essence of liberty and it only signifies a regression in civilization.

CUBA AND THE FREEDOM TOWER

R.C.- Miami is a city with a huge immigrant community, especially immigrants from Latin America, who keep their traditions alive and have a deeply rooted sense of belonging to their countries of origin. Political exiles are strongly represented within this group, especially Cubans and, to a lesser extent, Venezuelans and Nicaraguans, whose ideology is based on concepts such as patriotism and nationalism. On a symbolic level, they have reproduced their countries of origin on American soil. I think it will be very interesting to present this exhibition in Miami. How do you think it will be received? Do you think it could be misinterpreted?

P.B.- I do think Miami is perfect place to reflect on this topic. And yes, it could be misinterpreted in the sense that I’m not promoting any sense of patriotism, what some people may expect. Having said this, I think that when you immigrate to another country, you have rights and obligations, and among these rights is the duty to learn the language of the country of adoption, as integration only starts when you really learn the language. So, these communities are surrealistic because they depict a kind of dystopian no-man’s land that is neither home nor the land of adoption. And this only creates isolated, discriminated, and second-rate citizens, citizens that are imprisoned in their cultures of origin.

R.C.- The exhibition’s Miami venue is the Freedom Tower, called as such because in the 1960s it functioned as a processing center for many immigrants, above all for Cuban political exiles. This building is an icon. How do you visualize the dialogue between the historic and symbolic significance of this building and the concept presented by the exhibition?

P.B.- The Freedom Tower is a very symbolic monument, as you said. And I think that the dialogue of the works and the building will he highly interesting, not only because of the strong Cuban input here, but also in a more general sense: freedom cannot be promoted by constraint or subjection. The United States cannot impose a liberal democracy on other countries by force, even if most of us are convinced that democracy promotes positive values like tolerance, equality, and freedom. Nothing guarantees that there will be democratic regimes in Iraq and Afghanistan after the military intervention, and this is simply so because democracy as a system is very alien to their customs and religions; and this is also valid for other regimes like Iran, China, Belarus, and North Korea. What I’m trying to say is: it’s an internal affair.

And regarding Cuba, it’s fine to see all those Cubans marching against Castro on the streets of Miami time and again, although it’s something really strange to me. But I suppose that when the Cubans are totally convinced and willing to fight for democracy, they will do so and overrule Castro, as the East Germans did with Erich Honecker, the Polish with Jaruzelski, and the Romanians with Ceausescu. It would be hilarious to expect Europe or the United States to do the job!

R.C.- I have read that the exhibition will travel to museums in various countries. Could you share the upcoming venues with us?

P.B.- Well, as you know this is really an urgent topic, and as such, the show is having an excellent feedback. It will travel in February 2011 to the Cobra Museum in Amsterdam, Netherlands; in September 2011 to the MoCCA in Toronto, Canada; and in December 2011 to the Stenersen Museum in Oslo, Norway. And there are other venues with which I’m negotiating right now. Besides, we will also publish a book with international publisher CHARTA with several essays on this fascinating topic.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and an arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust (APT), New York, and associate editor of ARTPULSE. Some of the shows he has curated most recently are “Cinema X: I Like to Watch,” MoCCA, Toronto, 2010, and “The Non-Age,” Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2009. He is the author of The Art Fair Age (CHARTA, 2008) and editor of Sustainabilities (CHARTA, 2008).

“Patria o Libertad” is on view at the Freedom Tower 600 Biscayne Blvd. Miami, FL. 33132. (October 8 - November 20, 2010). Opening reception: October 8, 2010 7:00 - 9:00 pm

Raisa Clavijo is a curator and art critic. She is currently chief editor of ARTPULSE and ARTDISTRICTS.