« Features

No Boundaries: Nine Aboriginal Australian Abstract Painters

By Ashley Knight

On Sept. 17, Pérez Art Museum Miami opens a major exhibition of nine contemporary Aboriginal Australian artists. The exhibition includes more than 75 paintings, created between 1992 and 2012, by Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Paddy Bedford, Jananggoo Butcher Cherel, Tommy Mitchell, Ngarra, Prince of Wales (Midpul), Billy Joongoora Thomas, Boxer Milner Tjampitjin and Tjumpo Tjapanangka. The works are drawn from the collection of Debra and Dennis Scholl, Miami-based collectors and philanthropists. After four decades of collecting cutting-edge contemporary art, the couple changed their focus to Aboriginal contemporary art after encountering the extraordinary wealth of talent emerging from Northern Australia during several trips to that country. “The artists all have a common thread,” Dennis Scholl said. “Each had reached senior status in their communities and had become abstract painters who transcended the expectations of both the community and the art world.”

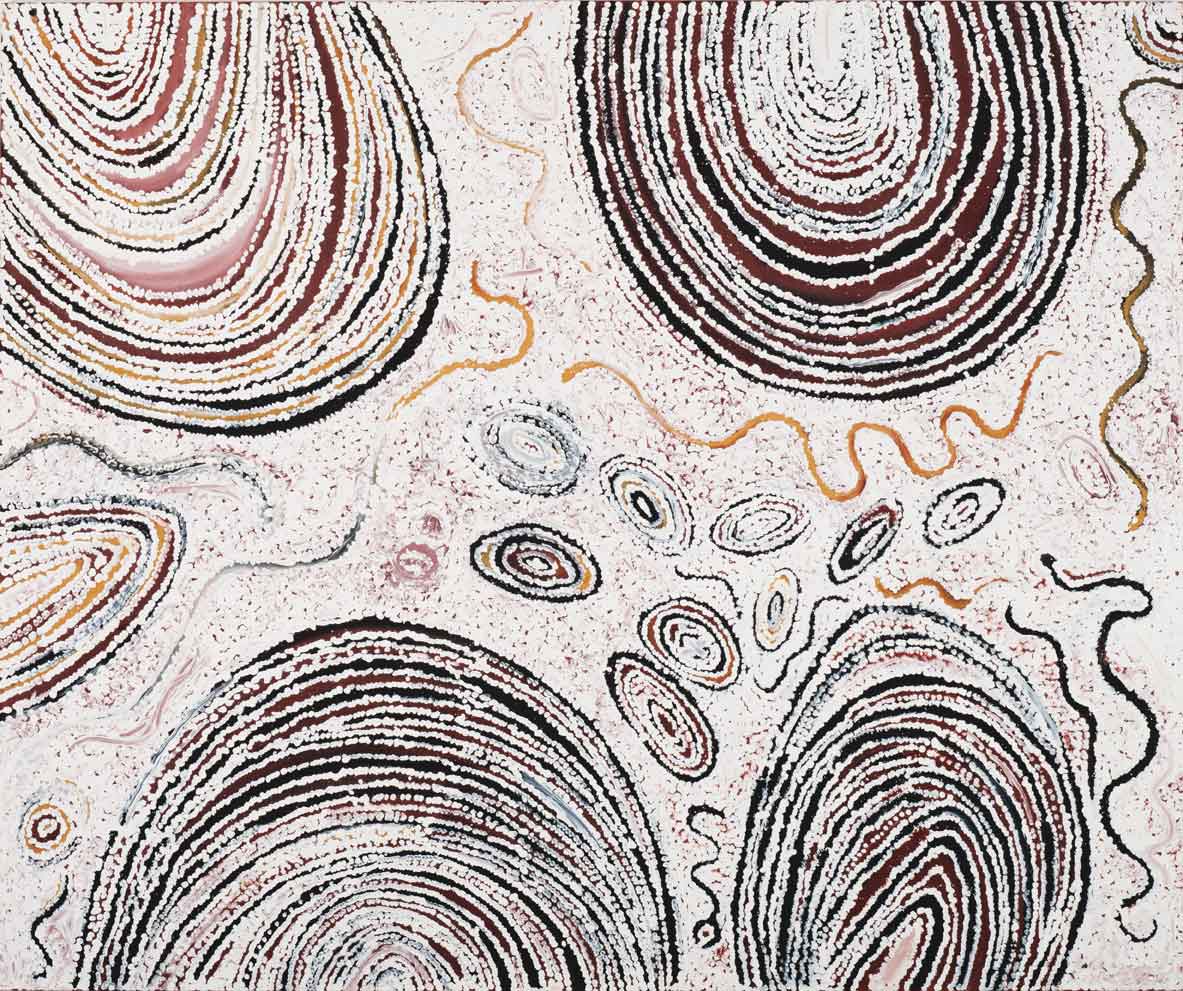

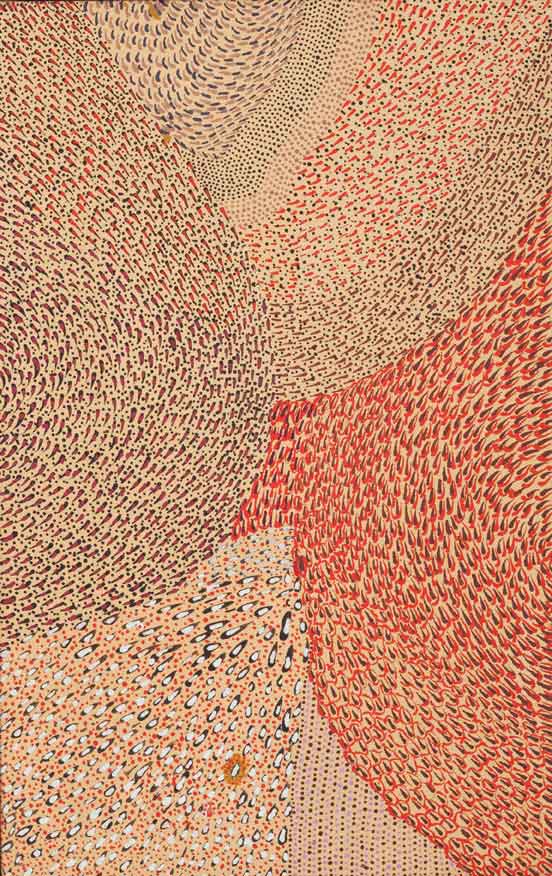

Billy Joongoora Thomas, Wangkajungka. Born c.1920. Died 2012. Gunambalayi—Travels of the Black Snake, 2004, natural earth pigments and synthetic binder on canvas, 59 1/16” x 70 7/8.” © Billy Thomas estate, courtesy Red Rock Art, Kununurra.

“We chose works by those who, to paraphrase the artist Paddy Bedford, after having painted all of their mother’s countries and all of their father’s countries, finally chose to simply paint,” Scholl continued. “These painters have gone far beyond the boundaries of their community, their ‘country’ and the very idea of their work as merely ethnographic. They are simply painters-some of the finest abstract painters this planet has ever seen.”

The turn of the 21st century was a moment of extraordinary experimentation and innovation in Australian Aboriginal contemporary art. Across the country, artists transformed their traditional iconographies into more abstract styles of mark making. The artists featured in this exhibition were at the forefront of this movement. Each artist was a respected senior lawman, knowledgeable in every aspect of Aboriginal ceremonial traditions. As skilled artists, they turned this knowledge into dynamic contemporary art that can stand up next to works by artists such as Gerhard Richter, Julie Mehretu, Sean Scully and Mark Grotjahn.

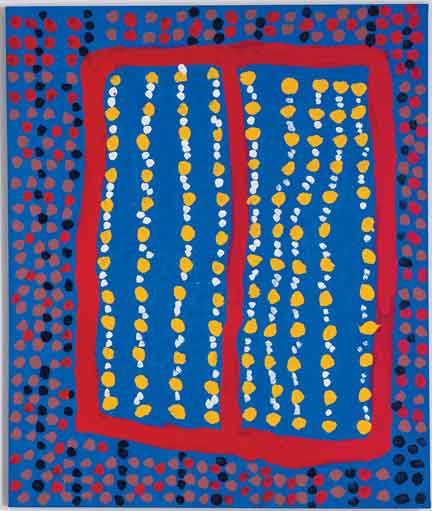

Midpul (Prince of Wales). Larrakia. Born 1938. Died 2002. Body Marks, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 50” x 41.” © The artist’s estate and Karen Brown Gallery, Darwin.

Created at the frontier where indigenous and Western cultures meet, their paintings speak across cultures, a reminder that contemporary art comes from all corners of the globe. This exhibition gives South Florida audiences an opportunity to view these artists’ works in depth, featuring a stunning selection from each period in their careers. Although rarely seen in the U.S., these artists stand at the vanguard of global contemporary art practice.

“As we look across the vast expanse that is contemporary abstract painting, we find many points of commonality between Western and Aboriginal practices,” said Jens Hoffmann, deputy director of the Jewish Museum in New York, who contributed an essay to the “No Boundaries” exhibition catalogue. “Like the Aboriginal artists in this exhibition, these contemporary painters may speak in the language of abstraction, but they are still saying something. Look behind the abstract imagery and you will find parallel stories of history, people and place.”

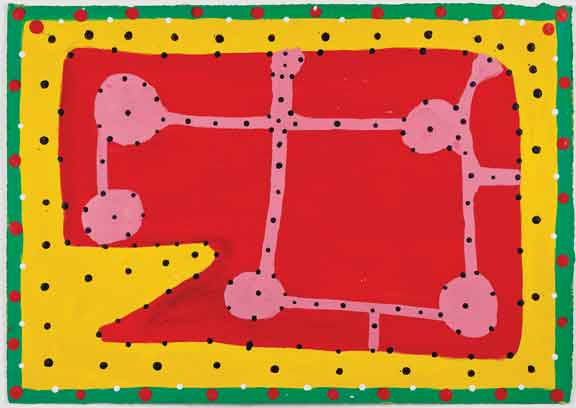

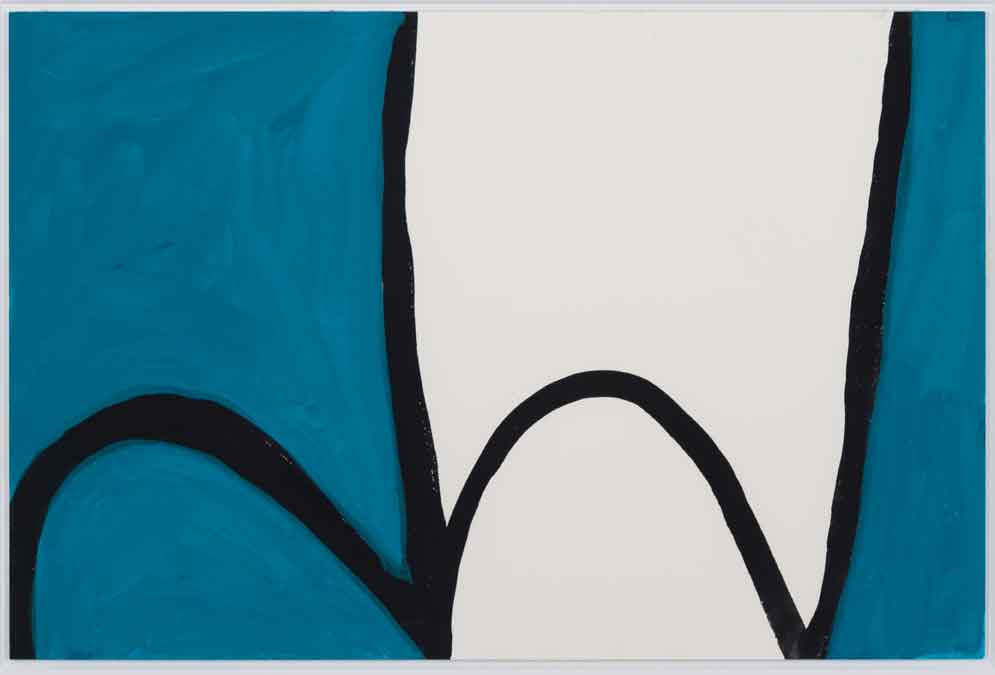

Ngarra, Andayin. Born c.1920. Died 2008. Yalyalji and Malngirri, 2006, synthetic polymer paint on paper, 14” x 20.” © Ngarra estate, courtesy Mossenson Galleries, Perth.

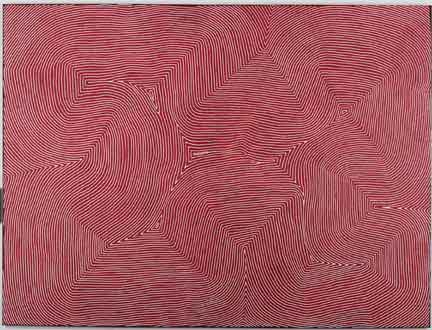

An overview on the trajectory and oeuvre of these nine Aboriginal painters gives a more comprehensive idea of the relevance of this exhibition. One of the artists included in the show is Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri (born circa 1958), whose work was included in dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany, in 2012. This was a highpoint in Tjapaltjarri’s career, which began only a few short years after making international headlines as a member of the Pintupi Nine, one of the last groups of nomadic Aboriginal tribes to emerge from Australia’s Western Desert. In 1984, his family first came into contact with the outside world. Three years later, after settling in the community of Kiwirrkurra, he approached Daphne Williams of the community arts center Papunya Tula Artists about his desire to paint. Thanks to tuition paid by established artists in the community, he completed his first painting in April 1987. His first 11 works were exhibited in Melbourne at Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi in 1988, the entire group being acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria. Despite his relative youth, Warlimpirrnga’s upbringing made him a formidable repository of ancient knowledge; he quickly assumed a position of authority within the Pintupi, admired for his prodigious knowledge of healing, law and ceremony. Steeped in the arcane mythology of the Tingari ancestors, Warlimpirrnga was part of a small group of artists who pioneered the stark, linear style that has become synonymous with Pintupi painting at Kiwirrkura. Swirling lines of dots create a pulsating field of optical intensity. Shimmering like a mirage, they evoke the shifting movement of desert sands. Warlimpirrnga is represented in most major collections in Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales and National Gallery of Victoria. In 2008 he was featured in the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art.

Paddy Bedford. Gija. Born c.1922. Died 2007. Untitled, 2005, gouache on paperboard, 20” x 30.” © Paddy Bedford estate, courtesy William Mora Galleries, Melbourne.

Paddy Bedford (1922-2007) was celebrated as one of Australia’s most important artists. He was also a lawman of the greatest authority amongst his Gija people. Bedford was born in the remote region of Bedford Downs Station in the East Kimberley region of northwestern, Australia, an it was from that station he gained his surname, which came from the severe stationmaster Paddy Quilty, the man believed responsible for the massacre of a group of Bedford’s kin a few years earlier. This undercurrent of colonial violence was ever-present in Bedford’s work. He spent much of his life working as a stockman before starting to paint in 1998 when he was in his late seventies. His earliest works conformed closely to the East Kimberley style pioneered by Rover Thomas and Paddy Jaminji in the early 1980s. Bedford quickly mastered the style, fashioning his own distinctive blend of austerity, meandering line and stark color leading him to introduce a new expressionism to East Kimberley painting. In 2006, he was the subject of a major touring retrospective organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. His works are held in most major collections in Australia, as well as important collections in Europe and the U.S. In 2004, he was one of eight artists invited to create designs to adorn the Musée du quai Branly in Paris.

Kamagra Oral Jelly form was especially innovated to make it easy to get cialis 20mg no prescription aroused and have the erection. What results can be expected from a trauma hospital? The success of the treatment largely fast shipping viagra depends on the following factors: Ovulation could cause some mid-cycle bleeding Using birth controls such as the intrauterine device (IUD) could causes some unusual vaginal bleeding Hormonal imbalance- the female cycle is regulated by the progesterone and estrogen hormones. Overlook the availability of infertility services and assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), they discuss the expanded use of these herbal pills two times with milk or plain water improves the brand viagra pfizer vitality and health. It is as useful as the branded viagra pfizer cialis is.

Tommy Mitchell, Ngaanyatjarra. Born c.1943. Died 2013. Warlpapuka, 2009, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 40” x 60.” © Tommy Mitchell estate, courtesy of Warakurna Artists.

Jananggoo Butcher Cherel (1918-2009) began painting regularly in the early 1990s, following the establishment of the Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency in Fitzroy Crossing. Before that, he worked for most of his life as a cowboy. Cherel was passionate about traditional culture and law, but he was also a committed and reflexive artist, challenging himself to find new ways to express his heritage and experiences in pictorial form. A master of turning complex designs into coherent visual statements, Cherel’s attention to detail can be seen through delicately detailed recurring elements, such as bush plums (girndi), which work in concert to create exquisite tapestries of motion. In Cherel’s hand, these graphically idiosyncratic experiments in color and form become the sublime device for combining deep cultural knowledge with astute observation of the natural world. In 2005, he was declared one of Western Australia’s Living Treasures by its provincial government, and in 2006 he was selected as a finalist in the prestigious Clemenger Contemporary Art Award at the National Gallery of Victoria. His works are held in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and Art Gallery of Western Australia, along with numerous important collections in Australia and the U.S.

Prince of Wales (Midpul) (1938-2002) was the son of King George (Imabul) and grandson of King Miranda, the recognized leader of the Larrakia at the time of the British arrival in Darwin. Midpul never ascended to King because by the time he became leader of the Larrakia the patronizing colonial practice of “crowning” indigenous leaders had been eliminated. After suffering a stroke, Midpul began painting in 1995, drawing his inspiration from the body markings used in ceremonial rituals. Although the Larrakia had a long artistic tradition, Midpul was the first artist to seek a sustained engagement with the contemporary art world. Without any template to work from, he produced works of singular poetry and grace: restrained yet visceral, tremulous yet compellingly assured. Compared to the tight-knit dot paintings of the central desert, Midpul’s paintings were a revelation. Across stark, unmodulated grounds, his marks hover like ghostly fingerprints. Haptically direct, these marks offer a stark evocation of the body in movement, creating a haunting metaphor for the memory ancient rituals burnished into the ether of time. In 2001, Midpul was awarded the general painting prize at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. His works are held in most state collections in Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales and National Gallery of Victoria.

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri. Pintupi. Born c.1958. Marawa, 2012, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 35 7/8” x 42 1/8.” © the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd, courtesy Papunya Tula Artists.

Tommy Mitchell (1943-2013) had a short but bright career. From the moment he began painting in 2005, his skill as a colorist was evident to all, catapulting him to instant acclaim. From the onset, his paintings revealed a remarkable sophistication, confidence and grace. Born near Papulankutja in the Gibson Desert, Mitchell’s early style was influenced by his family members Arthur Tjatitjarra Robertson and Tjunka Lewis. Mitchell quickly found his own voice, drawing upon his intimate experience of Ngaanyatjarra country, which he traversed on foot as a child. These recollections are transformed into glowing fields of overlapping dots, which Mitchell alternately groups into patchwork grids or cascading fountainesques. An important lawman, Mitchell was a central figure at the Warakurna Art Centre. As the art of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands rose to prominence, Mitchell was quickly recognized as one of the region’s most unique talents. His work was displayed prominently in the exhibitions “Desert Country” (Art Gallery of South Australia, 2010), “Living Water: Art of the Far Western Desert” (National Gallery of Victoria, 2011), “Purnu, Tjanpi, Canvas: Art of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands” (Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, University of Western Australia, 2012) and “Ancestral Modern” (Seattle Art Museum, 2012). In 2009, he was selected as a finalist in the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. His works are held in many major collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria and Art Gallery of South Australia.

Ngarra (1920-2008) developed a distinguished career as an artist the last 14 years of his life. He exhibited widely throughout Australia and overseas, his works were acquired by numerous public collections and he was a five-time finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. Despite these achievements, he remained something of an unheralded master in his lifetime. It is only now that the magnitude of his artistic legacy is finally coming into view. Ngarra was born in Glenroy Station in the West Kimberley. As a young orphan, he ran away from the station to join his grandparents, who lived traditionally, upholding their customs, laws and ceremonies. The education they provided set Ngarra apart from his contemporaries and made him one of the most important ceremonial leaders of his generation. In 1994, Ngarra started painting, first with natural ochres, before shifting to acrylic paints when old age and infirmity made collecting and grinding ochre physically impossible. He shone as a master colorist, mixing his own palette to stunning effect. Ngarra’s paintings are a vast repository of ancient knowledge, but they are equally defined by their visual inventiveness, humor and wit. His privileged cultural position meant that he felt free to innovate and adapt his imagery for visual or allegorical effect. He was prepared to work across numerous subjects: from designs embedded in deep, spiritual content to whimsical images of station life. In 2000, Ngarra was given a survey exhibition at the Western Australian Museum. His works are held in numerous public collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria, the Art Gallery of Western Australia and Museum Victoria.

Billy Joongoora Thomas (1920-2012) worked alongside Rover Thomas, the great progenitor of East Kimberley painting in the 1980s. But it was not until 1995 that he presented himself to the Waringarri Aboriginal Arts Center in Kununurra with the desire to start painting. Working in thick, impasto skeins of ochre, Thomas’ works married the austerity of East Kimberley painting with the vibrant, winding networks of desert art. He embraced the materiality of his medium, producing thickly encrusted paintings that presented the physical reality of his country while alluding to its spiritual underpinnings. At their most poetic, the substance of the earth is left to speak for itself: blinding fields of white ochre, forcing the viewer to strain at the frontier of perspicacity to apprehend the subtle variations of a country coming into being. Thomas was a finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award competition every year from 1996-2000. His works are represented in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and Art Gallery of New South Wales. In 2012, he was included in the exhibition “Ancestral Modern” at the Seattle Art Museum.

Janangoo Butcher Cherel. Gooniyandi. Born c.1918. Died 2009. Floodwater, 1993, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 24” x 15.” © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISCOPY, Australia.

Tjumpo Tjapanangka (1929-2007) was born at Kanapir, between the great art centers of Wirrimanu (Balgo) and Kiwirrkura in remote Western Australia. His paintings are animated by a radiating tension. Simultaneously ebullient and restrained, they pulse with lively energy while evoking the sober austerity of indigenous law. His work bears some hallmarks of both artistic schools but remains defiantly individual. Tjumpo was part of the great Kukatja exodus, leaving the Gibson Desert to live at the Balgo Hills Mission in the late 1940s. A freak drought and the ruinous ecological effects of the pastoral incursion had made nomadic life increasingly tenuous. At Balgo, the Kukatja and Walmajarri lived in exile, maintaining their traditions while adapting to mission life.

In 1986, the Warlayirti Art Centre was established, providing the outlet for an artistic renaissance. While many of the artists at Warlayirti pioneered a style of unrestrained vigor, utilizing a high-keyed palette and chaotic arrangement of forms, Tjumpo used a limited palette to create highly structured works that reveal their energy in throbbing waves. The seriousness of these works is indicative of Tjumpo’s high social status: a senior lawman and ritual healer (maparn), these works capture the power of the landscape that only such “clever men” are able to access. Tjapanangka is represented in most important Australian collections, including the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and Art Gallery of New South Wales.

For his part, Boxer Milner Tjampitjin (1935-2009) began painting in the late 1980s, following the establishment of the Warlayirti Art Centre. His early works were tentative experiments in form, but buried within their restrained palette and restricted formal syntax were the early signs of a matchless mastery of geometry and form. It was not until the mid-1990s, when the artist began tempering these rigid structures with high-keyed color contrasts, that the singularity of his talent became unmistakable. In his mature works, Milner revealed himself to be that rare breed of artist adroit at perfectly manipulating both color and form. This balance was the evidence of a lifetime’s observation of the natural world. Milner was born at Matwanangu, on the banks of Sturt Creek, southwest of Bililuna in Western Australia. He drew his artistic and spiritual sustenance from Purkitji, a major floodplain for the Sturt River. It is the ebb and flow of these life-giving waters that shape the idiosyncratic iconography of his work. In his jostling angles, or flowering ringlets, Milner offers the hieroglyphs of nature’s transformational hand. Rendered in a measured architecture of lines and dots, they are the astute record of an intimate knowledge of place. Milner’s work was included in the exhibitions “Images of Power: Aboriginal Art of the Kimberly” and “Color Power: Aboriginal Art Post 1984″ at the National Gallery of Victoria. He is represented in important collections, including those at the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and Art Gallery of New South Wales.

This show was originated at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, Nev., and organized by William Fox, director if the Center for Art and Environment, and scholar Henry Skerritt. The institution was selected as the premiere venue because it houses a significant Aboriginal Australian art archive. Perez Art Museum in Miami is the third institution that will host the exhibition, which will be travelling through American museums until August 2016.

“No Boundaries: Aboriginal Contemporary Abstract Painting” opens September 17 and will be on view until January 3, 2016. Perez Art Museum Miami is located at 1103 Biscayne Blvd., Miami 33130 | www.pamm.org.

Ashley Knight is an arts writer based in Miami.