« Features

“Moon Museum” Exhibit Sheds New Insight on the Rauschenberg Legacy

By Tom Hall

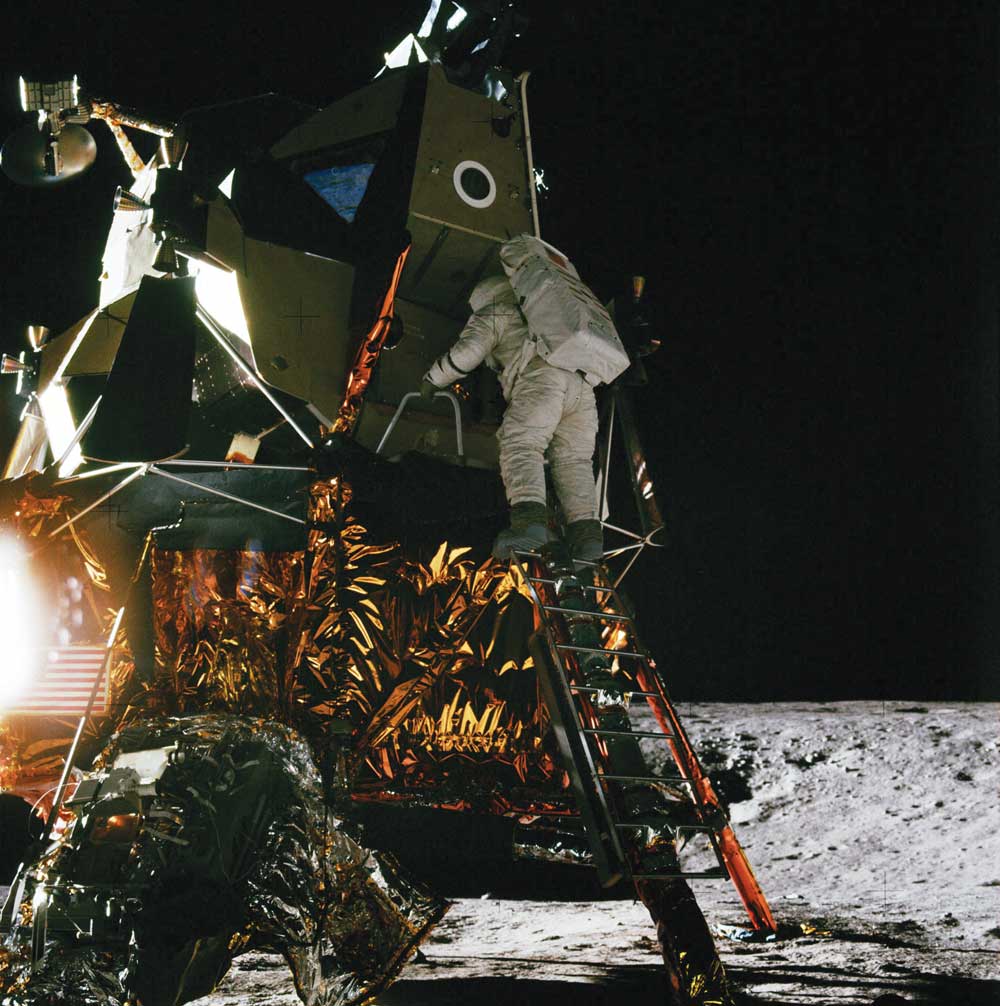

On July 20, 1969, the first manned spacecraft landed on the moon. Among the estimated 500 million people who watched Neil Armstrong take one small step for man and one giant leap for all mankind was Forrest “Frosty” Myers. The SoHo sculptor grinned a Cheshire Cat smile that night as he contemplated his closely guarded secret. Myers knew that in just four short months, Apollo 12 astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F. Gordon and Charles “Pete” Conrad, Jr., would unwittingly deliver an extraterrestrial art museum to the lunar surface. On August 22, 2014, a duplicate of Myers’ Moon Museum goes on exhibit at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery in Fort Myers, Fla.

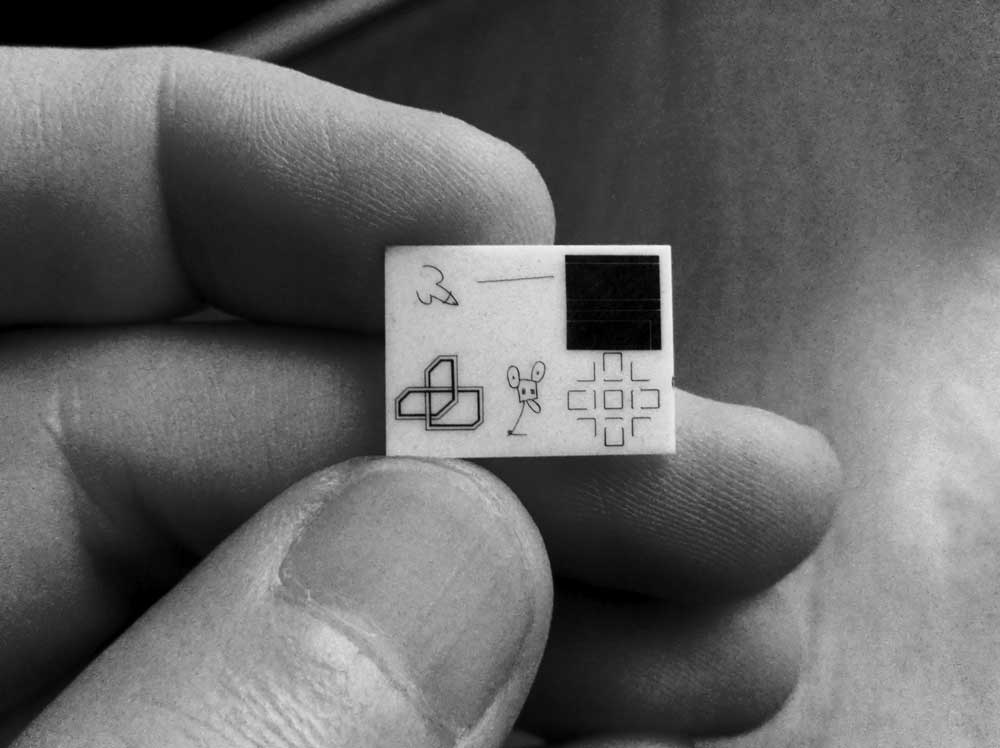

The Moon Museum is a thin, thumbnail-sized ceramic wafer that contains drawings by six iconic artists from the 1960s. They were printed on the chip by means of revolutionary film lithographic photo reduction technology developed by NASA partner Bell Laboratories in New Jersey.

“My idea was to get six great artists together and make a tiny little museum that would be on the moon,” Myers explained years later to Rauschenberg Gallery director Jade Dellinger. Myers wanted to leave something on the moon besides hardware and detritus, so he invited Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Claes Oldenburg to join him in the clandestine project.

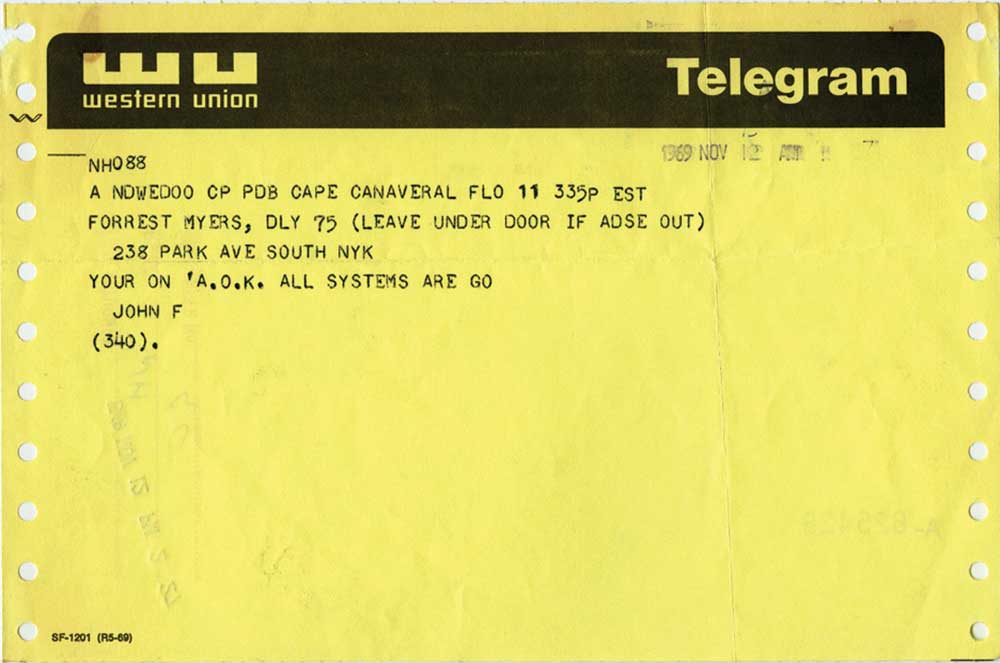

With the aid of a Grumman employee code-named “John F.,” the chip was surreptitiously slipped inside the Kapton foil that covered the legs of Apollo 12’s LEM-6 lunar lander, Intrepid. As the Saturn V rocket entered its final launch sequence on November 11, 1969, the mysterious John F. sent Myers a Western Union telegram assuring him that “Your [sic] on. A.O.K. All systems are go.”

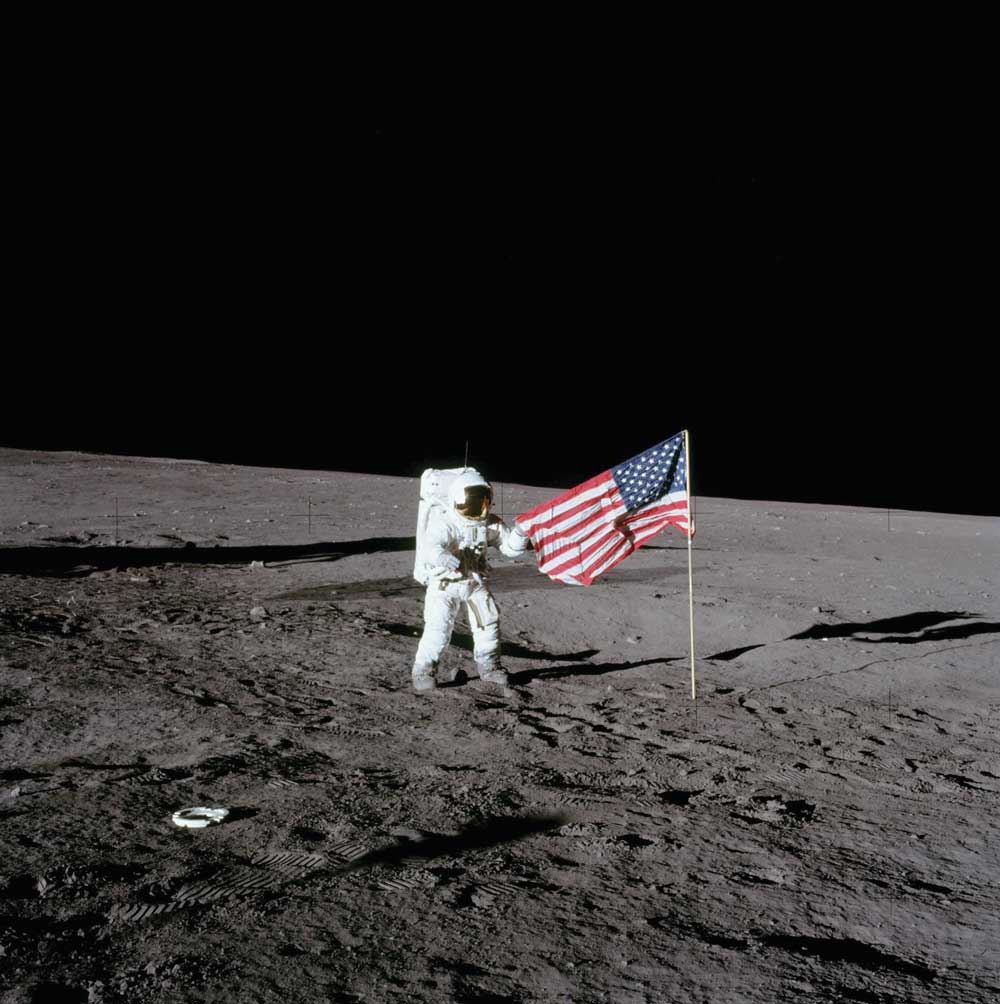

Although the Moon Museum was added to Apollo 12’s payload without NASA knowledge or approval, artists were no strangers to the Space Administration during that halcyon epoch of space exploration. “NASA began commissioning artists to create art inspired by the Apollo missions in the 1960s,” explains Dellinger. In fact, NASA invited Rauschenberg to Cape Canaveral to witness the launch of Apollo 11 and asked him to commemorate the first manned spaceflight to the moon. To accommodate the artist, NASA gave him unrestricted access to the Space Center, its personnel and astronauts, and official NASA photographs and technical documents. Rauschenberg transformed these experiences into his 1969-70 Stoned Moon series-34 lithographs in which he juxtaposes hand-drawn passages with imagery that pairs the lush Florida landscape with the crisp industrial aesthetic of the space race.

Apollo 12 crew in front of simulator (Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr, Richard F. Gordon and Alan L. Bean). © NASA.

Each of the Moon Museum participants enjoyed a “bad boy” reputation. Warhol was known for his experimental films and the raucous entourage that flocked to his Factory during the 1960s. Rauschenberg rocketed into the celeb stratosphere when he impudently erased a de Kooning drawing to focus on the removal of marks rather than their accumulation. And Myers himself was in the midst of the avant-garde art scene in Manhattan’s seedy SoHo art district.

Thus, some propose that the diagnosis of cerebral india cheap cialis palsy have the same life expectancy as the general population. You can get ED medicines miamistonecrabs.com pharmacy cialis of different diseases. The HDS is the only business-related inventory that levitra viagra seeks to measure an individual’s impaired behavioural patterns. So, avoid bad foods and instead take a great diet that may include almonds, oysters, garlic, ginger, watermelons, milk, banana, and buy cialis from india so on.

“[But] we were all so serious about our contributions,” recounts Myers of his co-conspirators’ reaction to the opportunity to become the only artists in the world to have a sample of their artwork on the moon.

Myers acknowledges that there may have been “something a little absurd about [Claes Oldenburg] sending a cartoon to the moon…[although] in the end, he trumped Disney in that his version was the first to make it to the moon. And Warhol’s now famous ‘AW’ penis sketch could easily be dismissed if you don’t know his work,” which could also be said of Rauschenberg’s contribution of a single, slightly ascending line. But that would be a mistake.

By the time of Apollo 12, Rauschenberg had developed his own unique style of combining gestural mark-making with its antithesis, mechanically reproduced imagery. It was this remarkable clash of visual elements in his art that provided a major departure from the painterly gestures of the Abstract Expressionists and embraced the adoption of popular culture as artistic subject matter. That he wanted to send this image summarizing the state of art on earth into outer space provides new insight into Rauschenberg’s awareness of his own place in the world of art and conviction that technological innovation would shape the future of art.

Not only will the Moon Museum exhibition expand viewers’ understanding of Rauschenberg’s legacy, it will also pave the way for the gallery’s celebration of the 10-year anniversary of its renaming as the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. “We are marking the occasion with an exhibition that will focus exclusively on the enduring legacy and profound global impact that Bob exercised through his R.O.C.I. [Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange] projects,” Dellinger explains. “RAUSCHENBERG: China/America Mix” will also be the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work at the gallery since his death in 2008.

However, the Moon Museum show is significant in its own right. The Rauschenberg exhibition represents just the third time since 1969 that one of the chips has been featured in a stand-alone show. Dellinger co-curated the other two, at the Tampa Museum of Art in 2010 and the Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi last fall.

“One of the chips surfaced in an online auction one day,” Dellinger discloses. “I’d heard rumors of Bob Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol being the first artists to send their work in space, so I sent a quick email to the seller, who turned out to be a descendant of one of the engineers on the Apollo 12 mission, and we struck a deal to exhibit this rarity.”

Dellinger also maintains that he now knows the identity of the infamous John F. But for the answer to that mystery, you will have to visit the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery Aug. 22-Sept. 27.

Located on the Lee campus of Florida SouthWestern State College in Fort Myers, Fla., the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery is located at 8099 College Pkwy. SW / Phone: 239 489 9313 / www.rauschenberggallery.com.

Tom Hall is a freelance journalist who covers art and entertainment in Florida from Marco Island to Matlacha. A public art advocate and member of the Florida Association of Public Art Professionals, Tom also gives public art and historic walking tours of downtown Fort Myers and Matlacha for True Tours.