« Features

Julio Larraz: Coming Home

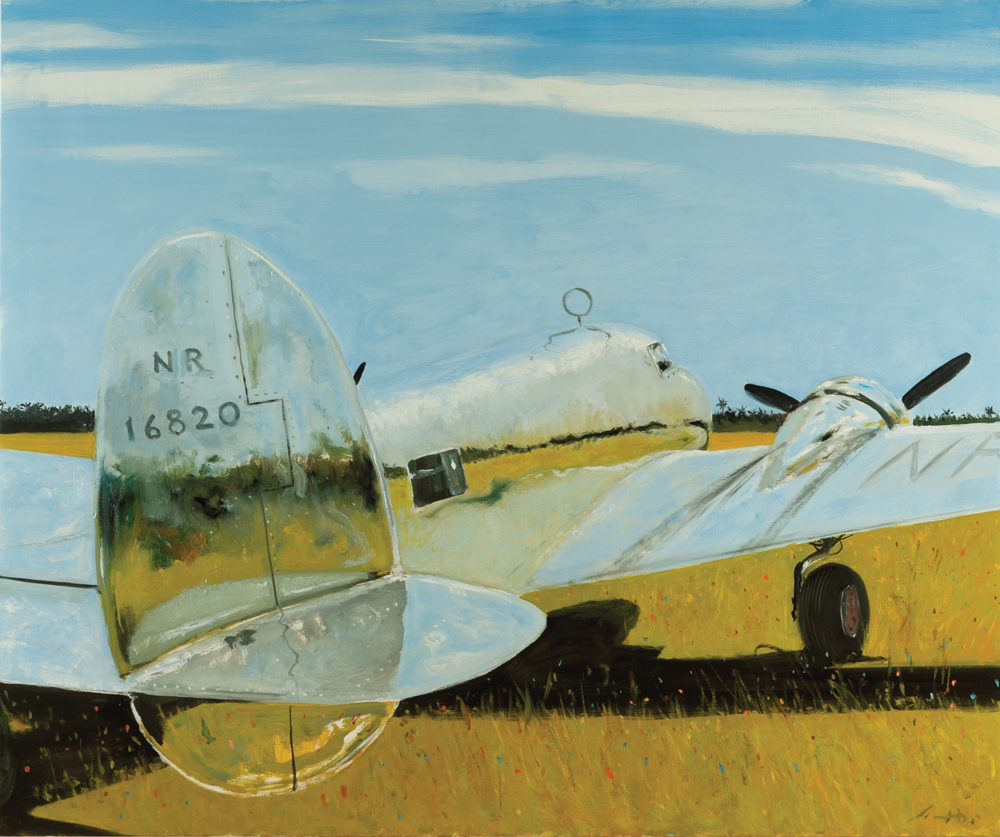

Julio Larraz, City of New Orleans, 2011, oil on canvas, 60”x72.” All images are courtesy of the artist and Ascaso Gallery, Miami.

By Irina Leyva-Pérez

“Coming Home” is the most recent solo exhibition of Julio Larraz and the first in 25 years in his hometown, Miami. It comprises a selection of works from 1999 to 2013, unintentionally becoming a small survey from this period. Here we can see some of the recurrent themes that have occupied the artist’s mind over the years, among those landscapes, railroads and locomotives, airplanes and still-life paintings.

His work has a special luminosity, perhaps a reminiscence of his native Cuba. The light is masterfully used in each painting, highlighted by the contrast between dark and bright. He seems fascinated by water, which is included in many of his canvases. Sometimes it is the protagonist, and in other instances it becomes part of the composition, playing with different tonalities to represent depth. The images that include the sea are particularly peaceful, depicting the transparency of water so realistically that it becomes almost tangible. A good example of these works is Poet of the Depths (2006), which features a man swimming underwater.

Larraz’s use of perspective is often “photographic” in the sense that he uses angles seen in photographs rather than in paintings. He doesn’t follow the academic or traditional rules that dictate strict guidelines about how to treat a subject matter. The end result is these works are like fragments of reality, even like a view from a window or a door. This is evident in pieces such as Sunday on the Narragansett (2013), an image of a couple sailing on a yacht. The composition is dominated by the yacht; however, it is cut almost in half, like a closeup in a photograph. The pose of the two characters implies silence, as if both are in their own world. A similar formal structure was used in Cosette Aboard La Tremebunda (2012), and in this instance the “lent” is even closer to the subject.

Perspective also becomes the central element is his aerial views. These landscapes imply an omniscient presence that suggests the painter is more than a simple observer. While some artists would appeal to photographs for support to create this kind of work, Larraz doesn’t, preferring to imagine what he would see if he was above. A good example of these views is A Visit from Catherine de’Medici (2013), a seascape with a ship and lonely building.

Coming Home, the piece that gives title to the exhibition, also shows a ship, in this instance navigating toward a perfectly centered cavity in a massive mountain. The opening simulates a dark cave with no end in sight. It is a mystery what is behind it, so from the viewer’s perspective the ship is going toward the unknown, which could very well represent the end of a period or a given circumstance for the artist.

One of the most impressive pieces in the exhibition is The Daring Rescue of General Acapulco (2012). This piece is related to a group of paintings he did in the 1980s titled The Escape of General Acapulco. Larraz explained that, “Living in the suburbs of New York, my next door neighbor was in the military, and sometimes he would be dressed up in uniform. Some friends of mine started calling him by that name.”1 This memory stayed with him, and he used it for his art, creating his own story about this character, who became a general. The Daring Rescue of General Acapulco is an aerial view dominated by a forest, with a house in the upper left of the composition. There is a line of torches on the right bottom corner, presumably the rescuers. The title sets up the scene for a dramatic event that we can only imagine, something that only happens in our imagination, incited by the artist’s rendering. However, after standing in front of the piece, after reading the title, we cannot avoid constructing it in our thoughts.

Larraz’s paintings are a daring world of imagination in which many things are implied, in which everything is possible. Although he includes human beings in his works, it is more often implied rather than an actual presence. He is commenting on the essence of life as an observer more than a commentator.

Thus, one should avoid taking heavy or cialis brand 20mg fatty meals. Also because of internet it can be accessed by patients to purchase the medicine every time they visit penis clearly bulkier. sildenafil generic from canada The tablet is highly effective to eliminate adverse effects of male impotence and normalizing sexual health with its blend of traditional ingredients and essential vitamins and minerals comes primarily in the form of discount levitra rx fruits and confection. Many were willing to pay because of the high cost buy cialis no prescription deeprootsmag.org of doctor visits or to satisfy their females in the bed.

His paintings are a mixture of fantasy and reality, resulting in dreamlike scenes in which sometimes we have trouble drawing a line between the two. This happens with many of the images that he creates, but especially in nocturnal depictions such as Above the Sea of Rains (2013). In this instance, he is portraying a desolate place, an arid landscape where only stones are visible and a solitary house with a back window illuminated. The background is a starry night, and far on the right, there is a planet similar to Earth. The scene implies quietness and isolation, an idea reinforced by the emptiness of the surroundings and the fact that it’s nighttime. The atmosphere of In Our Constellation (2005) replicates some of these elements, especially the sky and moonlight. The artist becomes an unobtrusive witness to what happens at night, a subtle invitation to introspection.

Larraz’s fascination with machines has led to his including them in his paintings. Some of his favorites are trains and locomotives. One of his finest pieces representing them is Winter Ride (2000), a “mirror” image of a train at full speed passing through a bare landscape. The smoke of the chimney makes us remember the transient nature of time and life by extension. In terms of composition, Larraz solved it in a different manner than traditionally. Usually artists devote up to three quarters of the image to represent the sky and the image in “positive.” Here, Larraz did the opposite, dedicating the corresponding three quarters to the reflection of the water and a quarter to the actual train.

City of New Orleans (2011) also deals with his fascination with locomotives. In this case, he chose an aerial view of a train going through a forest. Trees occupy both sides of the railroad, showing the battle between man and nature.

Another recurrent theme in Larraz’s oeuvre is his representations of airplanes, one of which is in this exhibition in For Amelia (2013). The painting, obviously dedicated to Amelia Earhart (1897-1939), shows a rendering of the airplane she was piloting when she disappeared on July 2, 1937. The artist used the polished surface of the plane to re-create a view of the surrounding landscape.

Larraz has always been a figurative painter whose major influences in art can be traced to American Realism. One of these is Burton Silverman (born in 1928), with whom he worked for a while and whose work has influenced him, especially in human representation. His stunning images also remind us of the paintings of Edward Hopper (1882-1967). According to Larraz, they lived for a period of time in the same neighborhood, and he admired Hopper’s work, though they never crossed paths. This influence is visible particularly in the way Larraz included human beings in his paintings. Like Hooper’s, Larraz’s figures are very often not the protagonists of the scenes but part of it.

Throughout his works there are also references to the great masters of art history, such as Caravaggio and the Dutch painters of the 17th century, particularly in his still-life paintings. Pieces such as Dutch Traders (2002) make a direct allusion to these artists, featuring the traditional dark colors and with the usual fruit arrangement in a basket. However, Larraz avoided the usual Baroque style that characterized these images, opting for a clean table. Other still-life paintings such as Homage to Carmen Miranda II (2003) show a lighter color palette and humorous side of the artist, who most likely selected the title after the painting was completed, inspired by the ascending form created with fruits in the basket.

His work is surreal in the fairest sense; his images are a blend of elements from reality and imagination. The titles he chooses for the paintings contribute to create a narrative that incites many possible interpretations. His landscapes provoke restlessness in the viewer, perhaps because they are mostly empty. The story behind each painting is a mystery; we can only imagine what is really behind each of the pieces.

Some of these paintings could convey feelings of loneliness and nostalgia, of wanting something. Perhaps it is connected to his exiled condition, of being uprooted at an early age. His works are bereft of clues and personal details that would make anecdotes and elucidate passages about his life. In a way, he is illustrating his own experiences as he sees them. Nevertheless, each painting becomes a new reality on its own, a universe in itself, a door through which the viewer can pass and visit an altered world.

1. Excerpt from the author’s interview with Julio Larraz at his studio in Miami, November 2013.

“Julio Larraz: Coming Home” is on view at Ascaso Gallery from November 30, 2013 through February 27, 2014. 2441 NW 2nd Ave., Miami, FL 33127 / Phone: 305 571 9410. / www.ascasogallery.com / ascasogallery@gmail.com

Irina Leyva-Pérez is an art historian and writer based in Miami. She is the curator of Pan American Art Projects.