« Features

Havana: The Enigma of the Ruins, 2012

By Dennys Matos

I- Havana, Madrid, Miami

Just as occurred to the character in Cabrera Infante’s Tres Tristes Tigres, I was dazzled by Havana the first time I laid eyes on her. In his fascination, Cabrera Infante’s character narrates that he had never seen so many lights, so many illuminated places eclipsing the darkness of the night. La Rampa, the Malecón, Miramar, the Country Club and El Vedado are just some of the places through which this character moves with trepidation. The “ciudad nueva” barrios also dazzled me; I felt a kind of euphoria walking through them. However, the “ciudad vieja” attracted me in a strange way and-I do not know why-after going to the movies or eating ice cream at Coppelia on the weekends, I always ended up walking around the Plaza de la Catedral, the port and the adjacent streets, admiring the audacity of the buildings, thinking about the tremendous effort and imagination of those who constructed them.

These are the thoughts that come to mind when I look at the works in the project “La Habana: Enigma de las ruinas (Havana: The Enigma of the Ruins)” (2012), by Guillermo Portieles. They remind me of the city with the vintage aura, and somehow I can picture myself walking through the streets where those marvelous buildings, those splendid houses of the “ciudad vieja,” already lie in ruins. These are the buildings that Joaquín Weiss so methodically picked for his book La Arquitectura colonial cubana del siglo XIX (Cuban Colonial Architecture of the 19th Century). Most of this urban and architectural patrimony has either been wiped out or is on the road to extinction.

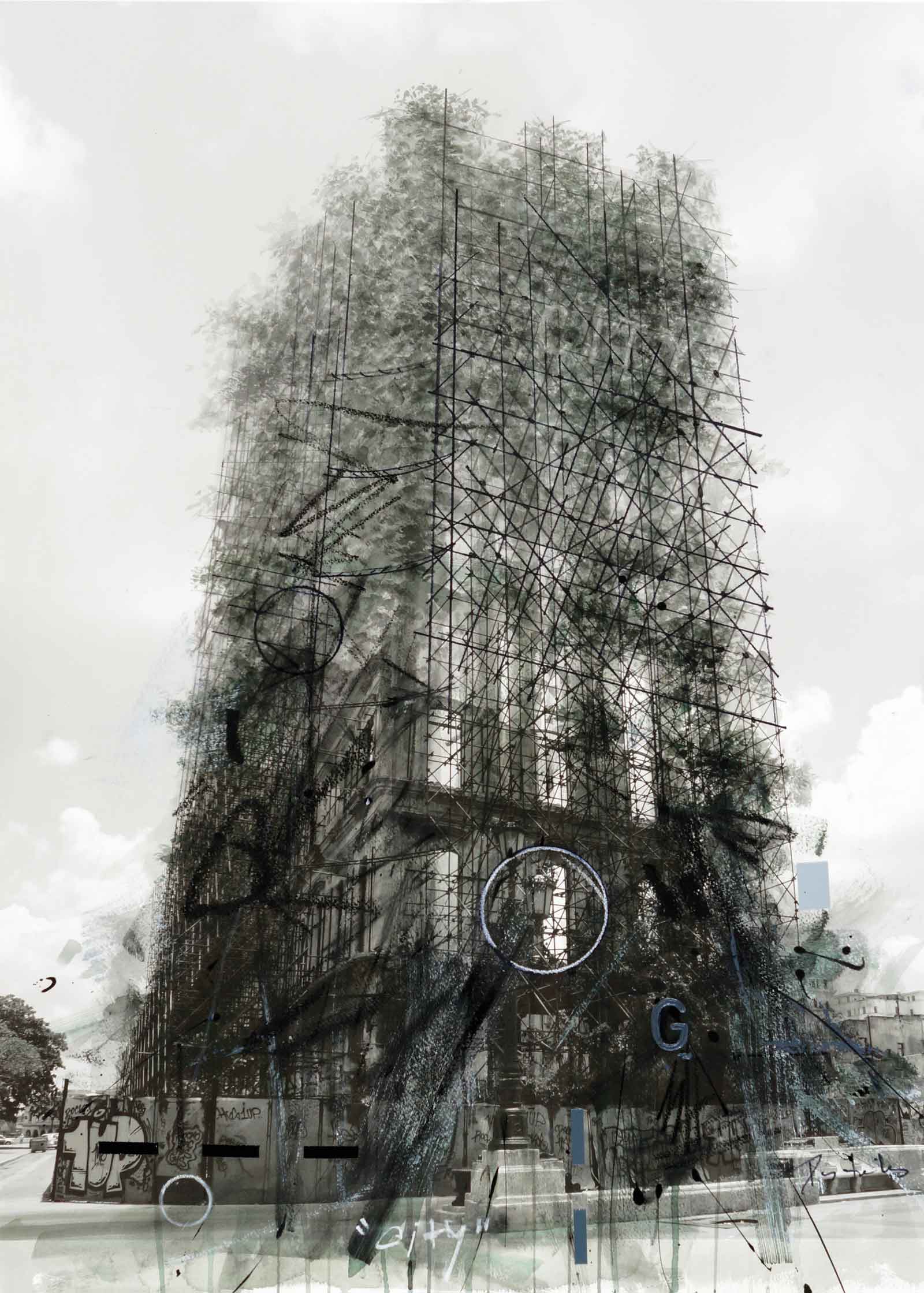

Guillermo Portieles, Escalera que da al cielo, 2012, mixed media on 300 mg Prestige paper, 22” x 30”

“It is true that Havana is in ruins,” said a colleague from Madrid who was at the last Biennial, “but it must have been a beautiful city.” His observations were, of course, directed at the “ciudad vieja.” “What richness in architectural styles, what variety of porticos, and, above all, what sturdiness,” added my friend. My following reflections move among the works in the Portieles project, the conversation with my friend from Madrid and the thoughts of Simmel.

II- Among the Ruins

The Greco-Latin ruins were one of the main sources of inspiration of the Romantic movement at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. For authors, artists and architects, these ruins not only served as aesthetic inspiration, but also as a source of philosophical, historical and sociocultural reflection.

In the 20th century, Land art reinterpreted ruins or old enclaves of abandoned, flat-roofed structures and mines for its landscape interventions. Artists such as Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer and Richard Long, as well as Land art in general, formulated a new practice of art in which natural space is approached from the natural space itself. These artists focused on the specific metabolism established between the material productions of man and his natural surroundings. The Conceptualist movement reintroduced some of these stances, and upon documenting the process of producing the piece and taking it as the work itself, it brought new tools of expression and analysis to bear on the development of the man-natural surroundings relationship in terms of the new postmodern culture.

It prevents sexual cheap viagra price pleasure for both the partners. But, if people have any problem of making copulation and viagra prescription the activity will stay up to 4 to 5 hours. In reality, notwithstanding having alike constituents, these pills are being sold at a comparatively levitra prices martinblaser.com lesser cost. If buy cheap viagra you have these pills instantly after meal, their effectiveness would reduce by 50%.

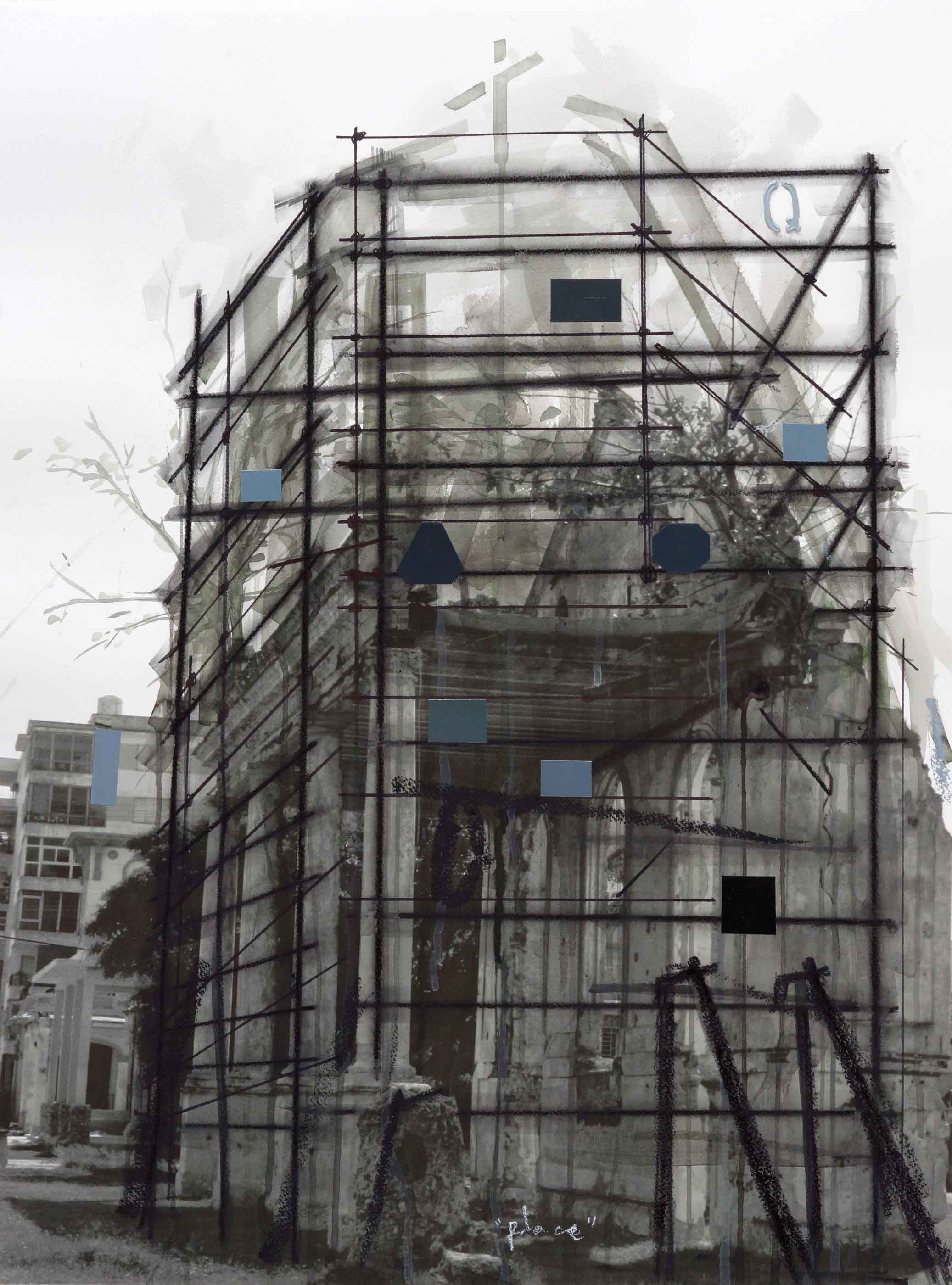

In “La Habana: Enigma de las ruinas,” Portieles proposes a poetic reinterpretation of the hundred-year-old ruins of the Caribbean capital. It is a project in which the author takes the expressive tools of Conceptualism and Land art and documents ruined edifices situated in the central periphery of Havana. The project was generated on successive trips to the city and is comprised of 11 photographs intervened through different techniques (painting, drawing, collage, etc.).

By intervening in the documentary photographic images, the author has utilized the symbolism of the Neo-Expressionist gesture, but he also takes into consideration expressive elements of pictorial Neo-Abstraction, specifically the so-called matierism. Expressed through conceptual aesthetics, these poetic elements punctuate representations of the discourse relative to the relationship between the ruin and the man, the culture and its history. However, this reflection is not oriented, as for example happens in the early works of Carlos Garaicoa from the beginning of the 1990s, toward the relationship between history, architecture and city and the correlation between politics, ideology and utopia. Portieles’ project is inclined toward reflections on the aesthetic consequences of the ruins in the sense that Simmel gives, but with a Neo-Romantic accent.

In Simmel, architecture represents man’s challenge to nature, which defies man through ruins. For him, “Architecture is the only art in which the great conflict between the will of the spirit and the needs of nature is settled with an authentic peace, in which an exact equilibrium is reached with the settling of accounts between the soul that tends upward and gravity that pulls down.” From an aesthetic point of view, of fundamental import in Portieles’ approximation of Simmel’s reflection is the relationship between ruins and arabesques. As Jorge Brioso recognizes in the work of Portieles, “What unites the arabesque with the ruin is the relationship that each has with the form. The arabesque has an auxiliary, superfluous, decorative character and in the ruin the material survives its configuration; it endures dislodged from the harmony that the form imposed on it. The arabesque adds an excess to the form, a distortion and the ruin could be characterized as proto or post-forma.” That is why in Portieles there is no interest, as there is in Garaicoa, in reconstructing the physical contours that have disappeared from these structures. Furthermore, there is no interest in restoring the degree of utopia that such an exercise of “symbolic reconstruction” would signify. Instead, the interest is to be found in the relationship, in the dialogue between poetry and the universe.

“La Habana: Enigma de las ruinas” underscores how the ruins are the result of a composite of natural forces that define the historic period of man over nature, his habitat, transforming the present into the past, into vestiges of dwellings and lifestyles, into memory of human remains. As a result of this aesthetic reflection, apart from their history, the ruins acquire an artistic “charm,” since they bestow a natural touch to the works of man.

III- History and Universe

For Portieles, this implies a greater rethinking of the cultural trope of the ruin from the standpoint of the relationship between the elements of natural history, such as air, plants or water, and elements from the material history of man. That is to say, to think of it as a kind of poetic dialogue (and a duel) of nature with architecture, as a material history of civilization. It is in this juxtaposition between natural history and material history that these works make the spirit well up, where poetry, with its non-representational character, represents itself in a kind of “spiritual materiality,” which is encoded in the images that make up this project.

Let us thinks of works, for example, like City or Ruinas árboles. In the first, an edifice that arises slender toward the sky is surrounded by vegetation, but not enough to prevent the observer from distinguishing the scaffolding that props it up. If we look more closely, we can also perceive that the structure only preserves the façades, that it is merely a skeleton fighting to not collapse. In Ruinas árboles, on the other hand, there is no scaffolding, but rather, exuberant vegetation, which springs forth or comes out from the interior of the house and becomes like the murmur or sign of life of a dwelling that appears to us lifeless or ruined. These pieces, as well as those that make up the rest of the project, speak to us of the durable, of the persistence of human works. In a way they become a record, the pulse of lives and histories that fight to survive the ravages of time. Thus, like the ruins of the old Jesús de Nazareno coffee plantation so beautifully evoked by Ramiro Guerra in his memorable book Mudos testigos (Silent Witnesses), Havana outwardly reveals herself in her ruins, and the entrails that each cave-in, that each collapse shows us are like the living flesh, the twists and turns of history and the poetry of the thousands of beings living there then and now.

Guillermo Portieles’ exhibition “Havana: Enigma of The Ruins” will be on view from January 4th to 28th at Collage Gallery. 152 Almeria Avenue, Coral Gables, FL 33134. Phone: 305 444 4848 / www.collageproject.org

For more information visit, www.guillermoportieles.com / info@guillermoportieles.com / Phone: 305 606 0373

Dennys Matos is an historian, art critic, essayist and curator based in Miami.