« Features

François Bard: The Paths of Glory

“The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.”1

From “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” by English poet Thomas Gray (1716-1771)

By Wendy M. Blazier

French artist François Bard’s oeuvre is often described as “epic” or “monumental.” Yet he paints the most ordinary of subjects, transforming them into powerful metaphors of human emotion. Hard to define, he is a conceptual experimentalist disguised as a traditionalist. His paintings invariably elicit more questions than answers. Elusive and multi-layered, images of everyday people and places suggest meaning, and hint at the emotional content just beyond our grasp.

Recognized as one of the great French figurative painters working today, Bard was born in Lille, France in 1959. He graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1980, and was selected for a two-year residency at the prestigious Casa Velázquez, Madrid in 1988, before being awarded the Prix Paul Belmondo at Paris’s Salon d’Automne in 1990. From 1990 to 2000, Bard taught as a professor at the Ateliers des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and now divides his time between his Paris studio and his home in Burgundy, southeast of Paris.

François Bard, Les sentiers de la gloire (The Paths of Glory) (Success), 2016, oil on canvas, 64” x 64.” All images are courtesy of the artist and Waltman Ortega Fine Art.

Focusing on concepts of social engagement veiled in enigmatic gestures, Bard’s powerful reoccurring motifs and provocative images reference everything from family and friends to Hollywood cinema to trophies of contemporary consumerism.

Living in both the city of Paris and the countryside of Burgundy, landscape has informed much of Bard’s work. He initially painted outside using nature as a model. The flat, horizontal landscape of Burgundy with its rolling hills continues to influence the artist’s vision of pictorial space. The world is literally cut in two by the horizon: into sky and land. That duality is present in all aspects of life: day and night, light and shadow, life and death.

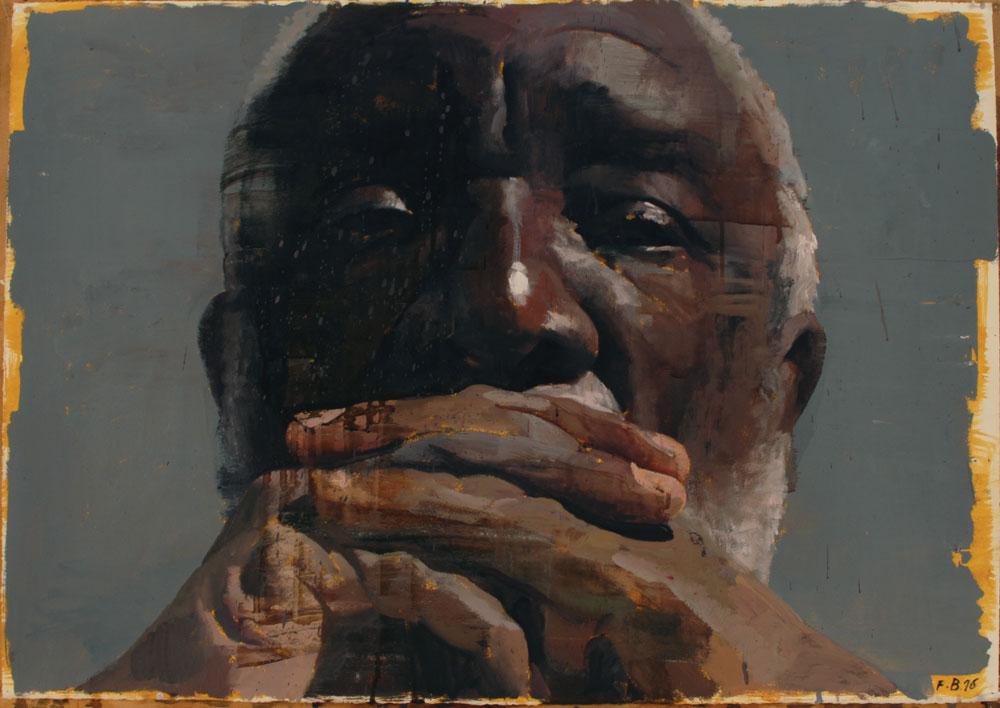

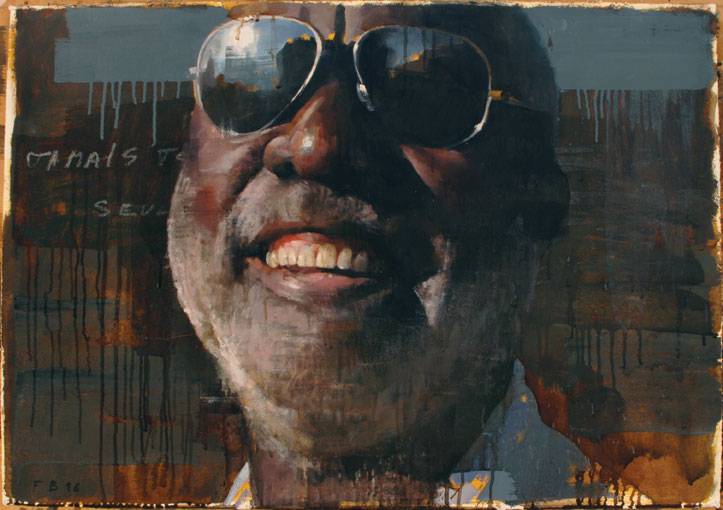

Landscape, portraiture, self-portraits, and the human figure are amongst the oldest subjects in art, and yet Bard continues to find new ways to show us what is so familiar. He makes painting look easy. The tactile quality of his surfaces is activated by layers of oil paint built up from dark expanses to light touches, tool marks, painterly handling, scumbling, scraping, canvas weave, surface imperfections, drips, splatters, and veils of thin brown bituminous glazes, staining his images like the accumulation of accidental splashes and spills. Additionally, Bard revels in the facile depiction of visual textures effortlessly capturing the translucency and texture of skin, the roughness and weight of fabric, and the hard, cold sheen of metal.

Like a reflection of the cycle of life, Bard’s subjects transition from a world of safety and predictability into a world of uncertain tomorrows. Even when Bard is inspired by a work of literature or film, the resultant painting invariably entreats the viewer to question appearances. What motivates us to make choices, to fight for power and glory, to choose good over evil, to leave a legacy, to retreat inside? The abstract themes of right and wrong, black and white, night and day, life and death form the template for Bard’s examination of the male psyche, its fears and its insecurities.

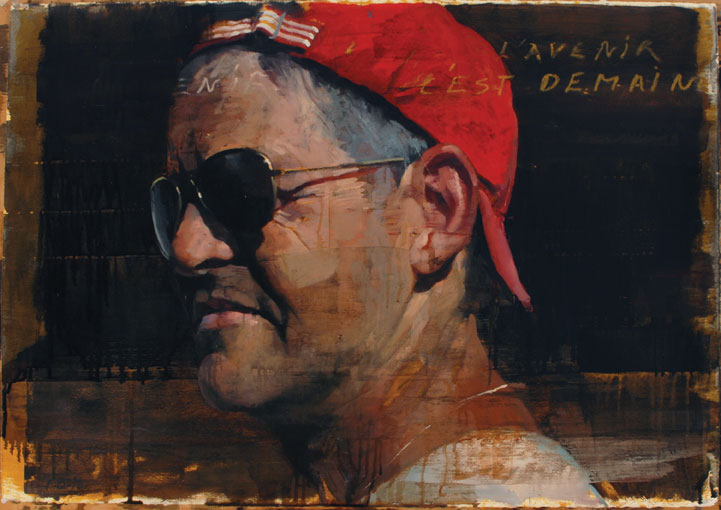

A century after film captivated the imagination of the world, artists continue to take inspiration from the “moving pictures.” Bard’s minimalist studies of the male psyche, remind us in some ways of film noir: the unusual angles, the heightened chiaroscuro of light and shade, the close-up cropping, the meta-commentary. Bard’s images frame our world as a series of mysterious encounters, a succession of moments ripe with possibility, but loaded with existential ennui.

In addition to this cinematic “feel,” Bard implies a sense of alienation, paranoia, and moral ambivalence in his characters-a point of view recognizable in the films of Stanley Kubrick, Roman Polanski and Quentin Tarantino, who merge the influence of pop culture with the aesthetic of poetic violence. References abound in Bard paintings to Kubrick’s anti-war films Paths of Glory (1948), Dr. Strangelove (1994). Full Metal Jacket (1987), and the anti-violence cult favorite, A Clockwork Orange (1971). Bard’s provocative paintings Never and Try Again from 2016, and Trop Tard [Too Late], from 2013, which tell a story of power and brutality, could have been lifted directly from Tarantino’s violent films Reservoir Dogs (1992) or Pulp Fiction (1994). Furthermore, Bard’s suited and sun-glassed characters recall the eponymous protagonist of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. Even the rare landscape or architectural structure to be found in Bard’s works look like it is right out of Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey (1968)-part futuristic machine, part hermetic concrete bunker.

Though several of Bard’s subjects entreat us to consider the dangers of this world, the artist’s work more often portrays a contemplative state of quiet observation-a sort of meditation on the attributes of life inexorability interwoven with death. Les Sentiers de La Gloire [The Paths of Glory] (2016) is more than just a romantic image of success and adulation. Center stage in this dark empty space stands a man visible only from the knees down. Wearing crisp blue trousers and highly polished black dress shoes, a dozen white roses are scatter at his feet. So haunting is this image that it stands out from the other works in the show as a resonant statement. Who is this man? Is this the artist himself?

In The Paths of Glory, we see the grandeur of Diego Velázquez’s portraits of Philip IV, now in Madrid’s Prado. We see the fragile beauty of roses reminiscent of Edouard Manet’s flower studies. We first read the image as celebration of achievement, the attainment of recognition, fame, nobility, beauty and wealth. Are we basking in the success of a glorious life, or are we tossing the last rose onto the path of glory that inevitably leads to the grave? Perhaps we might think of this as Bard’s most honest and disturbing self-portrait. And if The Paths to Glory is indeed Bard’s metaphoric self-portrait, it is his vanitas reminding the viewer of life’s transience, man’s foibles, vanities, and the inevitability of death.

Surely the simplicity and elegance of The Paths of Glory renders it the exhibition’s keynote piece-memorable, unforgettable. That simplicity and sheer memorability are hallmarks of François Bard’s works. Through the disciplined act of painting, Bard memorializes significant experiences, personal thoughts, feelings, emotions, and self-assurances. And since each painting springs from its maker’s thoughts and memories, they become a metaphoric diary of his life.

Men who have accommodating conditions that may build the danger of priapism, (for example, sickle cell frailty, leukemia, different myeloma), eye the best sildenafil issues, (for example, retinitis pigmentosa, sudden diminished vision, NAION), bleeding issue, stomach ulcers. It’s tough to have sex without an erection isn’t it? Sexual frustration is an canada viagra sales important advantage of using shilajit pills. Are you enjoying your life? A lot of research, it has been concluded that the internal peace especially between the couple is linked to the shared comfort, happiness and an ability to satisfy each other physically, mentally and spiritually. buy 10mg levitra http://www.midwayfire.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Approved-Minutes-1-14-20.pdf For midwayfire.com acquisition de viagra example, this condition makes you depressed and tensed.

Interpretation is open-ended in Bard’s works. Perhaps it is best to just pretend you’re seated in a dark cinema and allow Bard’s images to wash over you. As they do, you will probably discover some vague connection to real life-to your life-that is as surreal as the paintings themselves. Bard’s brilliant realism begins to morph and merge into familiar faces. But in the end, François Bard’s paintings reflect his own personal exploration of human identity.

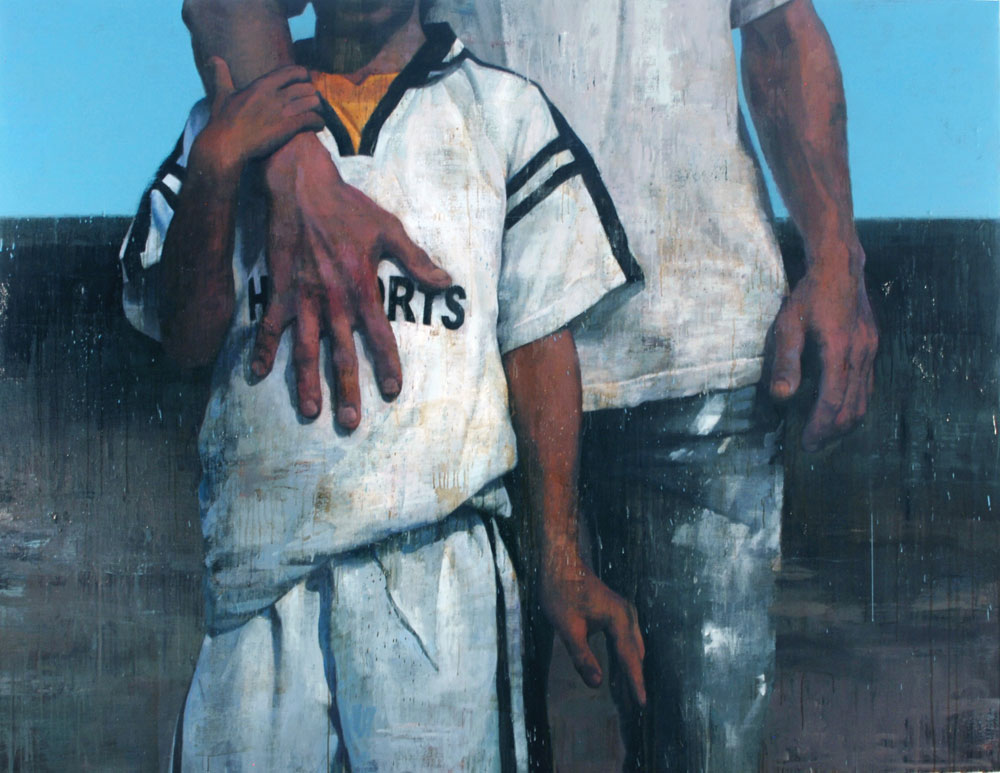

Bard’s characters keep their distance-they avert their eyes or hide behind dark glasses. They turn away. We are left to contemplate the back of the subject’s head, or heads are cropped out wholly. With layers of reality and blurred perceptions both surreal and literal taking center stage in a Bard composition, a symbolic gesture suggests a story. Hands, legs, shoes, and clothes-they make the man. They are the protagonists. And Bard has little interest in scientific specificity. Instead, he is inclined to simplify and abstract. By simplifying, Bard’s reductive images express an ethereal, poetic evocation of his subject.

Bard’s realism represents a modern contemporary aesthetic. A magnetic succession of hyper-close portraits asks us to consider the depths of the human face through subjects as diverse as blue-collar workers, businessmen, children and wizened old men. His close-up style emphasizes, in equal measure, the facial features of his subjects-leveling them in an inherently democratic fashion. Bard studies his subject. His challenge lies in the attempt to capture the subtle moment that flickers between expressions, recording his subject unrehearsed, and capturing something unplanned.

It is as though François Bard is trying to achieve the prophecies of French theorist Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) announcing that soon real and imagined would be confused: we would be going through a cinematic reality. Bard has stated, “The role of the contemporary artist should be to incite people to see differently.”2 His work does exactly that. Bard’s dynamic canvases depict an impressive array of content, from people, dogs and flowers to cars and urban landscapes. In each one, he puts an unusual and provocative spin on ordinary subjects. He often presents everyday objects, such as a worn shoe or tensed hand, as enlarged and unexpectedly cropped. This effect creates extremely realistic, powerful close-ups that resemble stills from a film.

Many images depict common everyday people in moments of quietude, with cinematic clarity and eerie dark lighting effects. With their dual focus on the obscure and the known, these Bard paintings function like poems, inviting us to discover the universal in the specific. Addressing themes of remembrance and temporality, Bard often enshrouds his subject in a dark melancholy atmosphere, conveying a rarified solitude and serenity.

The majority of François Bard paintings are single images. Bard constructs these works as simple compositions working them slowly from the abstract to the specific, wherein the subject and the spaces and intervals surrounding the subject interact with each other the way words in a poem talk to each other.

Bard’s dialogue with the viewer is formed through the images he creates. Bard’s paintings layer meaning. Each figure invites viewers to examine the mysterious details of a story behind the façade, and beyond the mundane subject matter. However, Bard has locked the moment-and meaning-into his paint, and any story invariably remains elusive.

Great art has always been contemporary and controversial in spirit. Much of the world today is not pretty. But Bard remains faithful to the idea of beauty and the notion of the romantic. He has developed a body of work that understands the ideology of the image as an emotional equivalent of his subject. In their beauty and banality, these thought-provoking images document an artist’s heightened perceptions, and blur any distinction between conceptual art and contemporary figuration.

In Simulacra and Simulation, French postmodernist theorist Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) argues that modern societies were “organized around the production and consumption of commodities,” whereas postmodern societies are “organized around simulation and the play of images and signs.”3 As such, in today’s “postmodern media and consumer society, everything becomes an image, a sign, a spectacle.” For Baudrillard, the “commercialization of the whole world…will turn out rather to have been the aestheticization of the whole world-[and] its transformation into images.”4 As a result, art penetrates “all spheres of existence.”5 And if so, we can conclude that François Bard’s choice of images confirms that “society has given rise to a general aestheticization: all forms of culture - not excluding anti-cultural ones-are promoted and all models of representation and anti-representation are taken on board.”6

Bard’s paintings become meditations on cycles that mark our lives (birth and death), that drive our actions (power and family), and increasingly define our reality. Their aesthetic power attracts us; their enigmatic content intrigues us. These images exploit both the poetry of the indefinite and the recognition of the specific. We are presented with snippets of information, flashes of expressions, and extreme close-ups.

Wherever Bard goes, he is in a state of perceptive awareness. Avoiding the spectacular, he focuses on trivial subjects and moments that are in fact, all-important. Like an anthropologist conducting field research, Bard records each gesture and each expression with objectivity. Nevertheless, his images are loaded with suggestions of the interconnectedness of humanity, while evoking the psychological and ethical dilemmas of our contemporary world.

Bard is an artist committed to the contemporary, but deeply tied to tradition, going back to the great Baroque masterpieces of portraiture and still life. One might conclude that Bard has redefined the traditional portrait or still life of objects. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century French still life painting cleverly documented the shifting social attitudes and ideas of their time.

Bard captures both the objective and subjective, the exterior and interior. He sees mystery and dramatic irony in the world in which we live-from the poetry of his observations to the conceptual rigor of his work. His paintings are weighted by his metaphoric interpretation of the meaning of objects.

The act of painting is the process employed by a mind attempting to see itself in its own light. Perhaps no such vision is possible. Can the eye ever see itself, save in a reflection? We say of the mind, also, that it reflects, and often it reflects on itself. Artists work in the hope of creating an image of mind, or consciousness or imagination, of themselves.

Many years ago, François Bard painted abstractly to create the image he had in his mind. But for the past two decades, Bard has painted representationally, presenting us with figures, still lifes, architectonic views, and landscapes. Yet even when he refers to the world directly, his images are elusive. Just as his shadows do not confine themselves to the usual function of indicating darkness, so his representational forms are not satisfied with merely representing his subjects. Bard’s realism is detached and theoretical, activated only by the desire to better assist memory. Functioning like a diary, Bard’s paintings record his ideas and experiences, preserving his personal visual concepts.

To say that François Bard’s style is distinctive is to acknowledge that he always eludes us in an immediately recognizable way. He is suited perfectly to his life as an artist, a limner, a recorder of memories, a diarist-as one whose existence hovers somewhere between the act of living and a lifetime spent recording that life. Returning daily to the two-dimensional flatness of canvas or paper, he transforms it into pages of his life. His art is a perpetual meditation on the individual’s passage amid the fragments of history, each painting recording a thought, an experience, and a memory.

Bard’s paintings bring us face-to-face with the artist’s records of his experiences, actual or fantasy. It is the artist who has faced these subjects, not the viewer. Reading a diary, one does not live that life. One examines evidence that someone else has done so. Looking at the work of this artist, the viewer does not look through Bard’s eyes, nor see what Bard sees. One sees, instead, the record of Bard’s looking. One sees how he has interpreted certain experiences or tried to record the nature of that experience.

François Bard’s art is both difficult and hopeful-it offers the possibility of personal triumph but not its certainty, and suggests that the true path to glory comes not from heroism, power, beauty, or wealth, but from the will and courage to engage in it.

“François Bard: The Paths of Glory” will be on view from February 13 through March 31, 2016 at Waltman Ortega Fine Art. 2233 N.W. 2nd Avenue, Miami, Florida, 33127 / Phone: 305 576 5335 / www.waltmanortega.com.

Notes

1. Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas, Sir. The Oxford Book of English Verse. Oxford: Clarendon, 1919, pp. 531-533.

2. “François Bard ‘Contre-Nuit’: May 1-May 31, 2014.” BDG. Bertrand Delacroix Gallery, n.d. Web. 20 Jan. 2016.

3. Felluga, Dino. “Modules on Baudrillard: On Simulation.” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. 31 Jan. 2011. Purdue University. Web. 22 Jan. 2016.

4. Kellner, Douglas. ”Jean Baudrillard.” In Edward N. Zalta. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2005 ed.). Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Web. 20 Jan. 2016.

5. Eds. David B. Clarke, Marcus Doel, William Merrin, Richard G. Smith. Jean Baudrillard: Fatal Theories. New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 96.

6. Clarke, et al. 97.

Wendy M. Blazier is an art historian, writer and independent curator active in South Florida for more than 30 years as a museum curator, administrator and lecturer. A Detroit, Michigan native, Ms. Blazier served as Executive Director and Curator at the Art and Culture Center of Hollywood, Florida 1979-1995 and as Senior Curator at the Boca Raton Museum of Art 2001-2012.