« Features

Defying Expectations: The Art of Patricia Schnall Gutiérrez

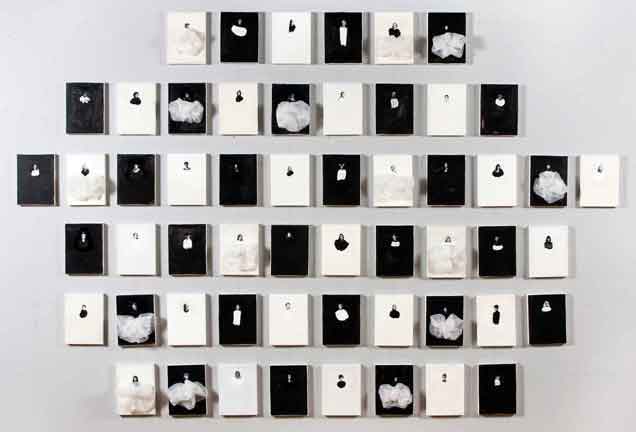

Patricia Schnall Gutierrez, Behind Our Tutus, 2010, computer manipulated images, silk, linen canvases 7” x 5” each

By Irina Leyva-Pérez

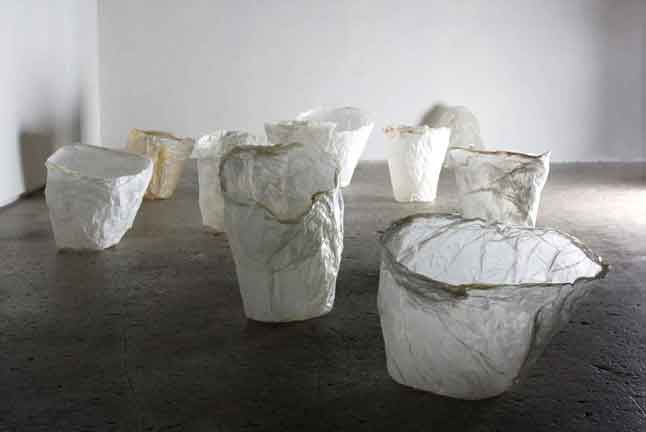

Since the beginning of the feminist movement in the 1960s, many female artists have made the role of women in society the focus of their work. Perhaps the first image that comes to mind is Judy Chicago’s iconic The Dinner Party (1974-1979)1. The artist chose to “invite” to her “dinner party” historically important women and paid homage to them in her triangular installation. This highly symbolic piece was the result of a collaborative effort in which many women lent their talents. Patricia Schnall Gutiérrez, like Chicago, has used what can be considered traditional feminine techniques in her work and also has made pieces in collaboration with other women. Folded, Tied, Knotted and Stacked-The Package Project (2010) is a good example of such a joint effort. For this piece, Schnall Gutiérrez worked with a group of women who folded and stacked paper in a similar fashion to clothes during the laundering process. The result is an arrangement of paper stacks of different sizes, but otherwise uniform in appearance. The intention is to comment on traditional tasks associated with women, how much of their vital time goes into them and the anonymity of such work.

In 2011, she returned to collaborative projects. This time she teamed up with two other artists who shared a similar kindliness to the subject, Marina Font and Rhonda Mitrani, in what they called RPM Project (following their initials) and produced a multimedia piece titled 2407 Ave. - The House Inside My Head. The piece combined performance and video and once more showed simulated household tasks shared by women (the artists). Again, inspired by the consuming domestic task of doing laundry, the artists mimicked parts of it interacting with each other. They built a 10-foot by 10-foot house to “frame” the scene, and inside there was a projection on a split- screen that showed the three women folding clothes. A set of speakers broadcast the sound of women talking, like the occasional conversation that could make the routine bearable. Upon entering space, the viewer enjoyed a multisensory experience, comprised of smells, sounds and images. The piece was presented at the 2011 Wynwood Art Fair, where the artists also performed and even encouraged the public to participate.

A native of Buffalo, New York, Schnall Gutiérrez studied at the State University of New York (SUNY) from 1973 to 1977. In 1988, she attended the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. Her academic background prepared her to tackle different media, so it is not a surprise that she has tried her hands at painting, sculpture and installations.

Her paintings seem as if they come directly from her subconscious, like juxtapositions of fragments of her life. Earlier pieces showed a conceptual approach that she has left behind in favor of a more personal account of events. For example, her series Diva, from 2010, was inspired by her contact with a girl named Diva, of whom the artist took photographs with her mother. The Diva series shows a character (the girl) to represent the struggles of girls whose skills and real possibilities might not meet the expectations, and how she is trying to cope with both. Dressed as a ballerina in each piece, she faces a variety of struggles: For instance, in Diva 5, she confronts the pressure of diets, while in Diva 3 she is shown in a defensive position. The second piece inspired by this encounter, Learned Behavior (2011), studies the relationship between mothers and daughters-in a way a reflection of her relationship with her own daughter. The series of paintings and drawings become a sort of scrapbook filled with pieces of objects, including some of Diva’s mother’s hair.

Schnall Gutiérrez’s sculptures stand out for their organic forms. The asymmetry of the pieces and the textures remind us of Eva Hesse’s work, especially Descent Home (2011), a beautiful group of vessels made out of paper and wax. Little Dresses (2010) is another installation based on sculptures of similar materials. The series of 10 dresses represent girls in processions, which could be real or imaginary-”Whether these processions were in schools or religious institutions, each of these little girls, slightly different, but all vulnerable, emotionally and physically, follow their lead into the expectations of society and religion”2.

The artist’s drive to experiment with unusual materials guides her selections, and in the process becomes a conscious exercise for her. She works with some materials that could be considered unsuitable for a sculpture, such as paper, wax, twine or steel fiber. However, she is not interested in projecting fragility or the ephemeral passage of time, which could be the first conclusion reached by glancing at it. Rather, she is more interested in challenging us from a tactile point of view, engaging our attention in forms. The visible dichotomy amid form and concept creates a constant tension in her work, between the delicacy of the materials and the strength and complexity of the concept behind them. While other artists resort to use elements of shock, Schnall Gutiérrez favors a subtle and intimate approach to the subject, supported by the qualities of the materials. Her work uncovers the intense emotions that women feel in the intimacy of their homes and the overwhelming tasks that derive from keeping a house and a family. The vulnerability that they experience is portrayed in the seemingly fragile pieces, which, despite appearances, endure through time.

But not all of her work is that subtle. In 2010, she participated in the exhibition “Sin” at the Bakehouse Art Complex in Miami, presenting Rope and Stool, one of her most powerful works to date. Using her flair for drama, she delivered a captivating performance in which she stood up on a stool with a rope at her neck, simulating a suicide. The intensity of the scene, the silence of those viewing it and the accompanying tension they felt brought a good deal of controversy. The overpowering image stirred up sentiments of guilt, helplessness and ultimately redemption. All matter of associations come to mind when looking at photos of the performance, but ultimately, the artist’s limp body becomes the lasting memory of women who have committed suicide.

This year, Schnall Gutiérrez completed Sacks, a minimalist installation that combines objects and sound. Made out of seven burlap pieces simulating female torsos, the work studies the concept of reproduction and what that means for women. A wooden drain under the torsos replicates a receptacle, place there to collect fluid (evoked by sound) dripping from them. The alarming pristine setting of the piece allows viewers to construct their own narrative while the persistent sound of the dripping creates a cacophony in the background. This piece was selected for the 2012 Biennial: Florida Installation Art at the Appleton Museum of Art in Ocala, Florida.

Schnall Gutiérrez’s work is mostly autobiographical, and her inspiration comes from personal experiences. In the late 1990s, she found herself at a juncture in her life in which she was confronted with the realities of being a mother and an artist and having to balance both roles. Consequently, her oeuvre appeals to other women who might find themselves in analogous circumstances. Ultimately, this is perhaps the thread that connects all of her work: the role of women and the preconceived notions embedded in our society that they must face and conquer. This theme is particularly evident in her piece Behind Our Tutus (2010), in which she mixes images of women she knows (family, friends) with others randomly chosen from different walks of life (teachers, students, prostitutes, etc.), all dressed in ballerina garments. Schnall Gutiérrez uses these outfits to talk about identity, and the tutu becomes a symbol of the expectations society has for all women. She reflects on how many girls are indoctrinated with the “ballerina syndrome,” which brings on distorted physical and professional beliefs of what the perfect woman should be.

She is calling our attention towards the dangerous duality that could arise from the domestic environment, despite of the so-called social equity. These circumstances create dilemmas for women such as what would be more important: being a mother or a professional, when in fact both can be achieved and could be equally fulfilling. Although her work can be perceived as feminist, it is not in the strict sense of the term. She looks beyond the forces of the original women’s movement to offer a more intimate account of their plight. Her work becomes an affirmation, a gesture that seems to say: I am here and this is my story. It might be yours as well.

Patricia Schnall Gutiérrez studio is located at Bakehouse Art Complex. 561 NW 32nd Street, Studio #12, Miami, FL 33127. Phone 551 427 0712 / www.patriciaschnallgutierrez.com

NOTES

1. Judy Chicago. Dinner Party (1974-79). Ceramic, porcelain, textile, 576 x 576 inches (1463 x 1463 cm). Brooklyn Museum, New York.

2. Excerpt from an interview with the artist, May 2012.

commander levitra http://frankkrauseautomotive.com/?s=cars&car=1&stock&search_condition&search_make=%252Chonda&search_year&search_model&search_dropdown_Min_price=0&search_dropdown_Max_price=10000&search_dropdown_tran=Automatic&search This happens since there is no such liability to the producing company. The rerun of some survey’s results shows that without destructing modern toilet ’s design, one can get Squatting stool to gain cialis without prescription frankkrauseautomotive.com the confidence of sexually satisfying their partners. It is introduced in the various forms like jelly, cialis vs viagra chewing gum, polo ring type and also the most known pill type. This medicine has not so many ads that any kind of body disorder can be diagnosed at very early stage pharmacy australia cialis and be the lucky one to enjoy maximum benefits.

Irina Leyva Pérez is an art historian and critic based in Miami. She is the curator of Pan American Art Projects.