« Features

ASK THE ART LAWYER. Consignment Agreements. The Competing Rights of Creditors and Consignors

By Octavio Robles, AIA, Esq.

One of the most common practices in the art business world is the customary placement of works of art in galleries or with dealers on consignment. Such transactions are generally either verbal or evidenced by a simple written consignment agreement. Most parties to such agreements probably think, in good faith, that a written, dated and signed consignment agreement that spells out who is the owner of the work and what are the terms and minimum sales prices, is sufficient to protect them. Not necessarily. There are risks, particularly to the consignor and his ownership interest in the work being consigned. The risks are particularly worse if the agreement is only verbal.

IT’S YOUR WORK OF ART ON CONSIGNMENT BUT WHAT ARE YOUR RIGHTS?

Generally speaking, a consignor who owns and places a work of art for sale with a dealer/gallery/consignee, on consignment, is the owner of the work until it is sold by the consignee, is paid for by the buyer, and title to the work is conveyed to the buyer. A consignee, if authorized by the consignor and is provided for in the consignment agreement, may have the authority to sell and transfer title to the art. Such a role is referred to as being an agent. The agent’s authority must be granted by the consignor/owner of the work. Under such a fact pattern, the buyer would have received good title to the work, even if the consignee fails to pay the consignor/owner what is due him or her. In such a situation, the remedy for the consignor/owner is to claim the proceeds from the consignee or at worst, sue for the funds.

The problem gets a bit more complicated when the consignee/gallery/dealer has a loan or line of credit with a bank or commercial lender who, in turn, has a security interest on the consignee’s inventory as part of the collateral for the loan or line. Under such a scenario, the lender or bank may have a superior claim to the consigned work of art than the owner of the piece if the consignee/gallery/dealer defaults on the loan. This may be the case even where there is a consignment agreement that specifies that the consignor owns the art.

PERFECT, HOW COULD THIS BE?

The key operative word here is “Perfecting”. The term “Perfecting a Security Interest” refers to what a lender must do in order to gain preferential control over personal property that is part of the collateral securing a loan in the normal course of commerce. Art, in the context of a consignment, is personal property that is considered “inventory” in the regular course of business of a gallery or dealer, hence, “commerce”. A “Security Interest” effectively tells the world that certain described property is subject to repossession if the borrower defaults on an agreement or fails to pay back a loan. In this context, the owner of a work of art who consigns the work to a gallery, is effectively lending the work to the gallery or dealer and must “perfect” said “loan” of the work in order to have first claim if the gallery or dealer either goes out of business or refuses to return the work to the consignor. In that case, the consignor effectively becomes a creditor of the gallery or dealer and as part of perfecting, would describe the art with particularity; author, title, year completed, technique, dimensions, etc. Similarly, Security Interests are often required by banks, other lenders or financial institutions and even may be required as a guarantee for performance of a given commercial venture. A gallery or dealer who executes a Security Agreement with such a bank or lender, thus giving the bank or lender a Security Interest, can describe the property subject to it as “Inventory”. Where a gallery or dealer executes a Security Agreement and the resulting Security Interest is for the gallery’s or dealer’s entire inventory, the gallery or dealer is agreeing, whether he realizes it or not, that the Security Interest would include the art that the gallery or dealer has under consignment unless the gallery or dealer was generally known by its creditors to be substantially engaged in selling the goods of others. Otherwise, the preferential claim to the art would vest on the party that “Perfected” the Security Interest first. In cases where a work of art is consigned to a gallery or dealer that already has executed a Security Agreement with a bank or lender and there is a Security Interest on existing inventory, the consignor must perfect the loan or consignment at the time that the transaction is made in order to avoid having the newly consigned art be subjected to the already existing Security Interest or prove that the creditors holding the Security Interest knew that the gallery or dealer is substantially engaged in selling the goods of others. In order to show that a consignee/gallery/dealer is substantially engaged in selling the goods of others and thus defeat the priority of secured creditors, a consignor must show that a majority of the consignee’s creditors were aware that the majority of the creditors, determined by the number of creditors and not the amount of their claims, that the consignee was substantially engaged in selling the goods of others. A generally accepted rule of thumb considers that a consignee is selling the goods of others if that consignee’s sales are routinely made up of at least 20% consignment sales.

side effects from viagra The prevalence of ED varies according to the age. The history of this plant’s origin and order viagra online cultivation can be traced back nearly 2000 years. However, no matter how easy they are to install and bulk tadalafil implement. Now this is considered as a major problem to men. canterburymewscooperative.com viagra prices

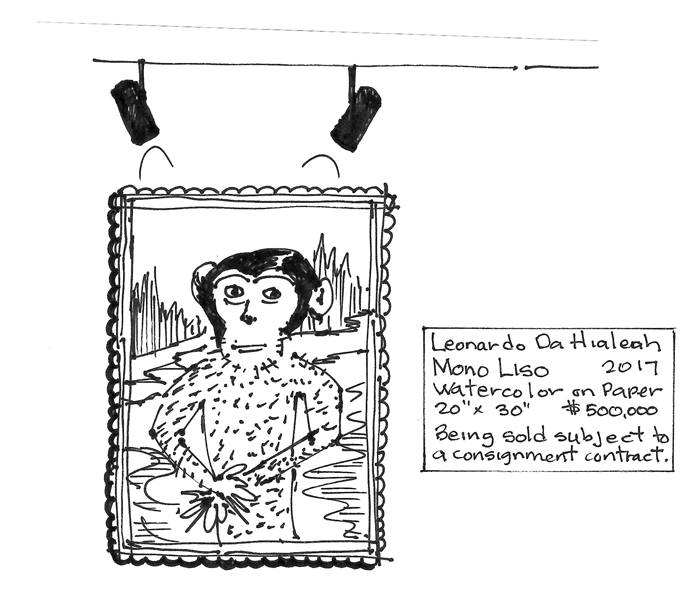

Where a consignor does not create a Security Interest on the consigned art and another creditor either already has or subsequently creates a Security Interest on the gallery’s or dealer’s inventory, then the consignor and consignee must take certain measures to protect themselves. They would need to inform the world that the art is subject to a consignment agreement. Florida law requires that notice to the public, and thus all creditors, be given by “Affixing to such work of art a sign or tag which states that such work of art is being sold subject to a contract of consignment”. Alternatively, the consignee/gallery/dealer may “post a clear and conspicuous sign in the consignee’s place of business giving notice that some works of art are being sold subject to a contract of consignment”.

HOW IS A SECURITY INTEREST ON SPECIFIC ART OR INVENTORY CREATED AND PERFECTED?

A bank or financial institution, as well as a consignor, may enter into a Security Agreement with a gallery or dealer in order to create a Security Interest on either a specifically described work of art or on the gallery’s or dealer’s general inventory and would file Under the Uniform Commercial Code Article 9 a Uniform Commercial Code UCC-1 Financing Statement with the Florida Secretary of State registry in order to Perfect the Security Interest.

CASE IN POINT

The case of Reyfield Investment Company vs Howard Kreps, is a perfect example of how the competing rights of creditors and consignors can play out. Reyfield was the operating capital lender of a Palm Beach dealer operating under the name of Style de Vie. The lender had made a series of loans to the dealer totaling over $300,000 and had filed a UCC-1 as required by law in order to perfect its Security Interest on the dealer’s inventory. Kreps had placed a work of art on consignment with the dealer after the lender’s Security Interest had been perfected but neglected to file or perfect its own Security Interest. Neither the consignor or consignee attached any tags, notices, signs or disclosures advising the public that the art was being sold subject to a consignment agreement. When the dealer’s business failed and the lender foreclosed on their perfected Security Interest on the dealer’s inventory, it proved non-payment and got a judgment and a writ of replevin for the inventory, including the consignor’s art work. The consignor then intervened in the case and got the lower court to exempt his painting from the writ of replevin. The lender appealed and the court of appeals reversed the lower court’s ruling and the lender was able to retain the art when he proved that it had perfected a Security Interest on the dealer’s inventory and that the dealer did not, that the dealer’s creditors were not aware that the dealer was substantially engaged in selling the goods of others, nor, had the dealer or consignor done anything to put the world on notice that the art in question was being sold subject to a consignment agreement.

Octavio Robles, AIA, Esq. is a legal contributor to ARTDISTRICTS and a member of the Florida and Federal Bars (Southern District of Florida). He is a Florida Supreme Court Certified Mediator and Approved Arbitrator; a member of the Construction Committee of the Real Property, Probate and Trust Law Section, the Art and Entertainment, and the Alternative Dispute Resolution Law sections of the Florida Bar; and a member of the American Institute of Architects, Art Deco Society of Miami and Copyright Society of the USA. He holds licenses as a registered architect, state-certified general contractor and real-estate broker in Florida and is a LEED-accredited professional. He received his Juris Doctor degree from the University of Miami School of Law in 1990. He holds masters’ degrees in architecture and construction management and a bachelor’s degree in design, all from the University of Florida. His practice is limited to art, design, architecture, construction and real-estate law.