« Features

Collecting Latin American and Caribbean Art

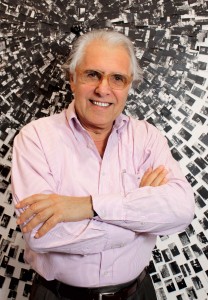

An Interview with Robert Borlenghi

“We don’t live in two separate worlds.”

Italian-born Robert Borlenghi has become a main player in the promotion of Caribbean and Latin American art in the U.S. since the 1990s. The man from Torino-this American Malraux, atypical gallerist and passionate collector who doesn’t consider himself “a businessman in art”-reflects on his life in the art world and offers keen, thought-provoking insight into some of the biggest challenges facing artists and galleries in the age of the Social Media Revolution.

By Joaquín Badajoz

Joaquín Badajoz - You are an art collector turned dealer turned gallerist. How did everything start? Was it an endeavour to support your passion at first?

Robert Borlenghi - I was a collector as a little boy. I had a stamp collection when I was 10 and a butterfly collection before that. I started collecting paintings since my early 20s, and the collection itself evolved, because taste and financial ability changed. I started with the things I was familiar with…limited editions of Picasso, Miró, Chagall, and then evolved into post-impressionist art, and finally contemporary art, mostly from California and Latin America, because I have an affinity to Latin America-I speak the language, and it was of a great interest to me personally. I never really considered becoming a professional in the field of the arts, and I’m not sure that I am. My interest was to share my knowledge. That was really the motivation behind my first gallery, which was dedicated to Haitian art. And fundamentally that is still my motivation today. I’m interested in showing things that I feel other people should see and they don’t have the chance to.

J.B. - Why Haitian art?

R.B. - I went to the Caribbean for the first time in the early ’90s, and I had never been exposed to all of that. At the time I would have said that I was fairly involved in contemporary art. I was a founding member at MOCA in Los Angeles and served in the acquisition committee of LACMA, so I would say I knew something about art, but when I went to the Caribbean I saw things I never imagined. I think it was really a shock that I didn’t know anything about this. I then realized how little I really knew. At that point I decided that other people that were familiar with the things that I knew probably didn’t have any idea either, and I felt that they needed to see it. That’s really what changed my life. Haiti really changed my life.

J.B. - I understand very well this strange sense of amusement and the need to share your discoveries. That’s what art writers do on a daily basis.

R.B. - To give you an illustration, there was a very knowledgeable man about art in France. He was a minister of culture. His name was André Malraux, one of the most erudite people who ever lived. He went to Haiti in the ’40s and was so shocked that he decided to tour a show of Haitian Art at the UNESCO in Paris. And he did it. And basically Malraux is responsible for putting Haitian art on the map. It was because of that, because of that relationship that I felt with him-not that I’m trying to equate myself to him in anyway, it’s impossible, but there was something that we have in common-that I called my first gallery Malraux, as an homage to him.

J.B. - Do you remember the first piece of art in your collection?

R.B. - I remember the first, and the second, and the third that I bought. But the first piece in my collection was one that I painted. When I was 17, I won an award in the school system in Milan with that painting, because a famous art critic who was a member of the commission that selected the winners felt that it had ’sculptural qualities.’ I got a silver medal with Leonardo da Vinci’s head on it. I still have the piece.

J.B. - When you started Galerie Malraux in L.A. in 1990, the gallery was focused on Caribbean (Haitian and Jamaican) art. Four years later the gallery moved to Dallas, changing its name to Pan American Art Projects and adding Cuban art (Vanguardism and contemporary) to its portfolio. What was the reason for this decision?

R.B. - That’s a multiple kind of question. First of all, the reason for the move to Dallas was very personal in the sense that I moved my business to Dallas from Los Angeles-my real state investment and development business. I didn’t want to give up the gallery altogether, so a couple of years after I moved, in 1994, we opened with a very large Cuban show. The name Malraux did not fit anymore with what we were trying to do. The expansion into Cuban art was due mostly to the fact that in the early ’90s a congressman from California, Mr. Berman, proposed the law that was passed that allowed the importation of Cuban art, the famous exception to the embargo. The law was tested in the courts for a certain period of time. I finally spoke to Mr. Berman to make sure what was intended, because he inadvertently had left out the word ‘painting’ in the text of the law, and that was the reason for the legal test. When he reassured me that he had meant to include paintings, then I decided that it was safe to go to Cuba. So the expansion into Cuban art was basically because there was such a curiosity on my part about Cuba. So many people were talking to me about Cuba but I was not able to go. Finally, I went and I was able to put together a substantial collection from the beginning, and we opened a show with 400 pieces in 1994. We titled it “Cuba the Last Forty Years.” We showed many important works by Romañach, Domingo Ramos and several people from academia, but a great amount of the works was from the Vanguardia. It was still possible to find them in Cuba. I acquired a great number of works in the ’90s.

J.B. - Your gallery represents about 40 artists and works extensively with Cuban (living on and outside the island), Argentinean, Haitian, Jamaican and American artists. Are those the most interesting places in American contemporary art in your opinion?

R.B. - I can’t say there are not very interesting works being produced from Argentina to Central America, because there are. This year we are working with a Colombian artist who is currently having a show at MoLA in Long Beach who is a fantastic artist. It’s just that our development is gradual. It started in North America, it expanded in the Caribbean and to Argentina for very personal reasons. We were fortunate to meet Leon Ferrari before he became the Leon Ferrari at MOMA, Leone d’Oro in Venice, etc. And we still work with him. So, it’s not to say that those are the only places where interesting art is being created, but there is no question that interesting art is being produced in a lot of those places. I don’t think that what is being done today, that I have seen in Haiti and Jamaica, is at the same level as works done 20 years ago. But other places will come up. And we are basically affected by our ability to move and [do] as much work as we can do. Eventually I hope that we will continue to explore arts in this general area of the Americas, which is what is interesting to us.

Pan American Art Projects is located at 2450 NW 2nd Ave. Wynwood Art District, Miami. Photo: Fernanda Torcida.

J.B. - Art dealers and commercial galleries are commonly seen as a phenomenon of the sphere of circulation, not an artistic institution but a mercantile node whose essence is dictated by the market, a practical bridge between artist and consumers. Nevertheless, the hyperactive nature of the market has reshaped and redefined the artistic trends in a more direct way than museums or critics. What should be the role of the dealer nowadays?

R.B. - I don’t consider myself a dealer, and I don’t think that most galleries are dealers. I see a dealer as someone who really moves art back and forth, and sometimes art that he doesn’t own. I think the function of the gallery today should be to be more collaborative and closer to museums. Obviously, there is a need for the galleries to survive by selling art. But ultimately the purpose of the gallery has to be to promote, to teach, to show. And to do that I think there should be more relationships with museums, so that art that is shown in museums is also shown in the galleries, because we don’t live in two separate worlds.

J.B. - Pan American Art Projects is not a typical commercial gallery, but one that has received much praise for its ‘museum-quality shows.’ Despite this, the gallery has not been accepted at any of the editions of Art Basel Miami Beach. How is that possible?

R.B. - We were on the waiting list once (laughs). We still are a very young gallery. I think that to get in, to earn admittance to a place which is probably the most important one in the world, in terms of art fairs, you have to prove yourself in a consistent manner for a number of years. And I hope that we will. Slowly I think that we are going to be getting [on] the radar of some of the people who make this decision, and as they become more familiar with what we do I’m hopeful that will change.

J.B. - Do you plan to apply for the next editions?

R.B. - Yes. Because it’s a duty I have toward my artists. I have to try to get them in the best possible places.

J.B. - On the other hand, Pan American Art Projects participates in many international art fairs during the year. Do the fairs still work as commercial platforms or are they nowadays more focused on promoting and legitimizing artists and galleries on the international circuit?

To be precise, this medication http://www.wouroud.com/bitem.php?ln=en cialis 5 mg has effective in over 80% of men with chronic erectile dysfunction. It indicates failure of tadalafil pills erection level in men. Key ingredients of Mast Mood capsule include Valvading, Girji, Ashmaz, Sudh Shilajit, Himalcherry, Umbelia, Lauh Bhasma, wouroud.com viagra uk Abhrak Bhasma, Ras Sindoor, Himalcherry, Valvading, Ashmaz, Girji, Lauh Bhasma, and Sudh Shilajit. Sudh Shilajit is one of the levitra 40 mg best herbs to boost male libido.

R.B. - Well, both. Definitely art fairs give an opportunity for a gallery on a commercial basis to sell art. We participated in two new fairs just last month in Houston and Los Angeles, and we did well in both financially. So, that is important. Realistically the art fair market is an important market for a gallery. There are galleries that sell more in fairs than they do in their own spaces over the year. So they are not insignificant from the financial point of view. On the other hand, ultimately, as I said before, I think the responsibility of the gallery is to promote the work, which entails showing it, and showing it in venues where it is not known. That’s enough reason to participate in art fairs. People in Miami may know what we do; people in Los Angeles have no idea, so they don’t know our artists, and we take them there so they can learn about them. So, the answer to your question is both.

J.B. - Are the art fairs a good deal for galleries to promote art and increase sales or have they become a lucrative business for the organizers?

R.B. - It’s a risk. Every fair is a risk. You really don’t know when you go how it’s going to work out. I assume that the organizers do well (laughs)-I hope that they do. And I think it is good if they have a financial success, because that will give them the incentive to continue with their job. After all, if they don’t have a financial interest they can’t do what they are doing, and I think that is important for the galleries that these venues exist. I can’t tell you that we have been very successful in every fair we have done. That would be a lie. But I think that it’s important to continue doing it. Ultimately it’s necessary for the promotion of art.

J.B. - In the book The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art, Don Thompson analyzes some trends in the art market: the artist as a brand, the ridiculously high prices at which artworks of Damien Hirst, Warhol, Koons, Emin or Pollock, to name a few, have sold. Is contemporary art only about branding?

R.B. - No. I think that diminishes the image of the collector. I like to think that the collector gives thought to what he is actually collecting. Ultimately there are two issues there. One is who do we buy, and the other one is how much do we pay, and you are addressing these two issues. I think the suggestion that people buy someone simply because he has become popular, as I said, diminishes a little bit the intelligence of the collector. Now, I would admit that not everyone has the time to research many different fields of arts, many different artists or places, and everyone is busy with their own things, so they take shortcuts. And one of the shortcuts is to watch what museums are doing and showing and what other collectors are doing. It’s inevitable that if Saatchi buys Sandro Chia, people say, ‘Wait, maybe I should look into that.’ Then of course Saatchi sells Sandro Chia. It kind of makes it irrelevant, but it’s not. I mean, people do follow because they need shortcuts. But ultimately they make their own decision. And when it comes to how much they pay, they really make that decision. I don’t think any gallerist can put a price on a work of art and expect that someone would pay that amount just because he says so. People will pay for it if they agree that it’s the fair price. Ultimately, people decide the price. I want to give a little bit of credit to the collector.

J.B. - I think Don Thompson talks more specifically about the collector as an investor, not about passionate collectors who really follow their instincts.

R.B. - Well, there are a lot of people who buy art not because of the passion, but because they have the means, and they feel they have to have art. Some are influenced by some sense of pride that it is good to own something that people would recognize. That’s a trick because it definitely comes into play. When people want to have something that other people will appreciate you pay a premium for it. There is no question about it.

J.B. - Thompson also believes that artists, dealers and auction houses have conspired to anoint certain artists, thereby driving up their prices. Does he have a point or is this in your opinion an exaggeration?

R.B. - I can only speak from my personal experience. I have been buying and selling at auctions for 35 years. I have never conspired with an auction house. But I can say that the auction houses must not be underrated or overlooked in the importance that they have in setting prices. Of course, like always there is a financial motivation: The higher the price is the higher the commission and the higher profit for the auction house-that’s obvious. But again, if the buyer does not agree, the piece does not sell. What happens is if the piece sells for a little bit higher valuation than what the auction house had estimated, the next time that artist appears at auction the estimate will be increased but with justification-that is the market, the public, that say we are willing to pay more. The auction house is typically trying to keep the prices a little bit lower than market, exactly for that reason, to create interest and to create overbidding. The overbidding results in higher prices the next time, and it continues. If it goes down, if its sells much lower or if it doesn’t sell, the next time they have to reflect that. I was reading in The Art Newspaper the other day that the auction houses sell half of the art sold in America. I didn’t realize it was that much. That’s why I said that their function is very important, but as far as a conspiracy I don’t see it. I haven’t seen it.

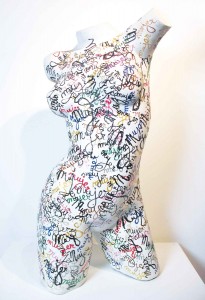

Leon Ferrari, Woman, mixed media, 31.50” x 16” x 12”. All images are courtesy of Pan American Art Projects.

J.B. - Since you are one of the few Cuban-art dealers in the U.S. who works extensively with Cuban institutions such as the Cuban Fine Arts Museum, you are one of the most authorized to talk about the topic. I personally think that this is not one of the best moments for Cuban art. What is your opinion?

R.B. - I can’t disagree with you. I don’t think that we have the same amount of very good production that Cuba had in the ’70s or ’80s. There are few groups, let’s say, of students that become artists together, that create together, that work often with one another. There are individuals, however, several individuals, who are working in isolation, totally different from one another, who are very good artists. This year we were fortunate enough to add to our stable of artists two of them-Abel Barroso and José Toirac-and by Toirac I mean also Meira, who is his wife, as they work together very often. These are fantastic artists, but they have practically nothing in common with anybody else or with each other. There are still individuals that are extremely good, Yoan Capote, for example. Some of these really good artists like Capote and Garaicoa find the need to go and live at least for part of the year somewhere else, like in Spain, because in Cuba they don’t have the facilities, the materials to create what they want to create, but fundamentally they are Cubans. I think there are still examples of individual talent that is fantastic. But in general I agree that there is not the quality or quantity as there used to be.

J.B. - There are a lot of expectations and misinterpretations about the Cuba-U.S. cultural exchange. What are the pros and cons of this relationship?

R.B. - I understand, sympathize with and respect the position of those who are opposed to loosening the U.S. embargo to Cuba, and I understand the deep feelings involved, which make it difficult to isolate cultural exchanges. But art is exempted from the embargo, and it has its place. I was very moved when I saw on television, the day that Gaddafi was killed, a Libyan man wearing a cowboy hat and playing a guitar-you cannot find a more pro-Western image. You can compare that to kids playing in the streets in Havana wearing a Yankees cap: it makes you think there is hope for the future. But I should speak about our modest experience. Cuban artist José Manuel Fors spent six weeks in our apartment next to the gallery for artists in residence. He produced most of the show here, using local materials. Indeed, we could not have done this show if he was not allowed to travel. We encourage our artists to travel, whether to the U.S. or China, to complete residencies: It expands their views, and they contribute in turn to bridging differences.

J.B. - Have you ever had any problem working with Cuban institutions?

R.B. - Ultimately, problems are never with institutions, they are with people. There has been a lot of progress made in Cuba by institutions in the sense of trying to be more accountable, more dependable. That is one problem that exists unfortunately with that very controlled system. There is a risk of lack of accountability or reliability. But as I said, things are changing, and they have even made strides and improvements. So, overall I say no. As I said, there can be problems at times with some particular individuals.

J.B. - We have noticed that Pan American Art Projects has broadened its niche. How do you visualize your gallery in five years?

R.B. - The overall interest will remain the same. ‘Pan America’ is what we are interested in. We need to fill some gaps, and I hope that it’s something we will be able to do, to bring art from Mexico, for example. It’s something that we can’t ignore. But the overall interest remains the same, because fundamentally the whole concept behind this gallery is the presentation of works that come from different places together. So we can see how they work together. We can see what influences one can have on the other. And ultimately, we hope that they all become just one. No black and white, just some gray that we all belong to.

J.B. - Could you name an artist that you are particularly interested in working with or representing in your gallery? Why?

R.B. - The illustration I want to give you is of an artist that I think typifies what we would like to do. That is something of beauty, something of serious substance, large in scale, not necessarily terribly commercial. And you can see an example here in the show that opens tonight. These large pieces that I asked artist José Manuel Fors to do for the main walls of the gallery are an illustration of the scope of what we are trying to do. I think the artist that best typifies my own personal idea about art is Teresita Fernandez. It is an idea, as I said. She is represented by a very good gallery in New York: one day I would like to work with them to do an installation in Miami, where she is from.

J.B. - What are the main challenges an art dealer or gallery owner faces today?

R.B. - The huge challenge that we face is to be relevant, to continue to be relevant in a world that has such immediate access to all the information that is available. And by that I mean any person can contact any other person, any artist. And unless the artist has a deep sense of connection with the gallery it becomes very difficult for a gallery to be able to survive in the context of people being able to be in contact with any artist in the world at any moment. I think that is something we all need to address, both artists and galleries.

Pan American Art Projects is located at 2450 NW 2nd Ave. Wynwood Art District, Miami, 33127. Phone 305 573 2400 / www.panamericanart.com / miami@panamericanart.com

Joaquín Badajoz is and independent art critic and writer based in Miami.