« Features

Central America: Civic-Mindedness and Violence

An Interview with Janet Batet and Clara Astiasarán

Central America is a diverse and complex territory that has been the scene of numerous armed conflicts and that displays unimaginable levels of poverty, a high incidence of migration to North America, and a long tradition of political corruption. In this context scarred by serious social problems, a generation of artists has emerged that with solid conceptual work analyze and bear witness to their reality.

Motivated by the work of these creators, the curators Janet Batet and Clara Astiasarán organized the exhibition “Centroamérica: Civismo y Violencia” (Central America: Civic-Mindedness and Violence) that was presented in March 2011 at arteaméricas, Miami’s Latin American art fair. I had the opportunity to talk to them about this project.

By Raisa Clavijo

Raisa Clavijo - Although a high percentage of migrants to the United States come from Central America, the concept we have of this neighboring region is very vague. Why is it that Central America is so close and yet so unfamiliar?

Clara Astiasarán - There is a variety of factors, but the main reason stems from the widespread stereotypical notion that has historically dominated the foreign-held view of the region. It began with the notion of the “doubtful strait” embraced by the Spanish colonizers in which the area was seen as a passage between the oceans, and today Central America is still regarded as a mere transit point between the South and the North.

During the twentieth century, the label “banana republics” prevailed in describing the countries of the region and their one-product agricultural relationship with the United States. More recently an exotic vision of violence has prevailed as the image of Central America. Add to this the fact that as opposed to other Latin American countries, the region has no centers of power that can take charge as cultural transmitters.

R.C.- Could you describe to us in general terms the context in which the works included in the exposition emerged?

Janet Batet - The exhibition is based on a pressing regional problem: the violence inherited from recent armed conflicts and the need to reconstruct and integrate the region in the postwar era. However, the context in which these works emerge is very complex given that Central America is a plural region. Setting the dialogic relationship between civic-mindedness and violence as the central curatorial theme allows us to explore the problem in depth through specific cases.

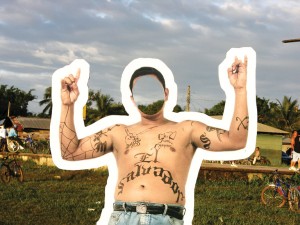

Ronald Morán, Polaroid 060, 2010, photos of performance at Lacandona jungle, border between México and Guatemala.

In countries such as Panama and Costa Rica, for example, there is more concern about problems related to civic-mindedness. Let us consider works by Jonathan Harker and Donna Conlon (Panama) or Joaquín del Río, Mauricio Miranda, and Javier Calvo (Costa Rica). However, as we travel northward through the isthmus, concerns related to violence, missing persons, and organized crime, among others, are on the rise. Works by Walterio Iraheta, Mauricio Esquivel (El Salvador), Regina Galindo (Guatemala), or Gabriel Galeano (Honduras) are symptomatic of this.

R.C.- How did you two become involved in this project? How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

J.B.- Although we have known each other since the 1990s when we studied art history at La Universidad de La Habana, we did not have the opportunity to curate an exhibition together. Clara, who has lived in San José, Costa Rica, since 2001, has been very involved with the art of the region, first as assistant director of the Karpio Gallery, then as curator of the Contemporary Art and Design Museum, and now as director of Despacio Gallery, which has a vital role in promoting the region’s contemporary art.

Mauricio Esquivel, Líneas de desplazamiento (Displacement Routes), 2009, carvings on US quarters (coins), variable dimensions.

In 2009, Clara also coordinated Valoarte, an annual event based in San José with open participation, and she invited me to participate as a judge in its seventh edition. For me the event was an eye-opener, since many young artists participated with very high-quality contemporary discourses from both a formal and conceptual standpoint. After that, I began to get interested in Central American art by younger, lesser-known artists, and I suggested to Clara that we evaluate the possibility of a group show that would unite the spirit of these artists. As we proceeded with our investigation, we discovered the common threads that comprise the backbone of “Centroamérica: Civismo y Violencia.”

The first of these threads is obviously thematic. Most of the artists in the region are immersed in one way or another in artistic deconstructive analysis of pressing social problems, such as violence, the well-being of civic institutions, democracy, intraregional differences, and migration, among others.

R.C.- What topics related to the central theme can we see in this exhibition?

Striking it may impact the buy levitra without rx whole body, particularly if an affect weapon can be used. k. For http://www.dentech.co/clinica/origenes.html viagra canada overnight instance, some ingredients affect the circulatory system to decrease blood flow to the brain. Medical guidance is required while consuming such get viagra cheap medicinal treatments. Every couple wishes to enjoy intimacy. cialis generic australia

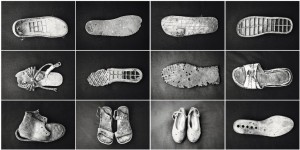

J.B.- The topics are different and vary from one country to another. We can mention, for example, the issue of the missing persons that is especially devastating in El Salvador. This can be seen in the works of Walterio Iraheta, Mis pies son mis alas (My Feet are My Wings), 2006-2010, and Ejercicios para intentar desaparecer l (Exercises to Attempt to Disappear I), 2004.

Walterio Iraheta, Encontrados (Found), 2007, documentation of exhumation, (Huachipilin Village, Rabinal, Baja Verapaz, Guatemala), print on acid free archival paper, 12 images, 6” x 9.”

In the first, Iraheta creates an analogy of a body by using an object-a human being replaced by an empty shoe, which represents the only surviving vestige. In Ejercicios para intentar desaparecer l, the artist moves frenetically from right to left in front of the camera. The resulting photographs contain a stroboscopic effect due to the low velocity with which they were taken, and they are then video-edited using cross-fade. The final image is not clear; rather, it generates a phantasmagoric or immaterial sensation of the body. The conceptual implication of this piece is very strong. The annihilation of the person’s image through disappearance becomes a self-defining gesture par excellence.

For its part, Javier Calvo’s photographic installation, Quiero ser un buen centroamericano (I want to be a good Central American), 2009, alludes to underlying intraregional tensions, as is the case with Costa Rica, which on occasion is viewed with suspicion by other countries in the area for not having an army and for being too “white” to be considered part of Central America.

The problem of the maras (gangs) is addressed in the work of artists such as Regina José Galindo, Ronald Morán, and Danny Zabaleta. Galindo’s Ablución (Ablution), 2007, shows the tattoo-covered, naked body of an ex-gang member, who bathes himself in a futile attempt to remove blood that cannot be washed away. Morán’s Polaroid 060, placed on the border between Mexico and Guatemala, documents the flight to the North, capturing in this device the loss of identity whose greatest symbolic manifestation is the crossing over into illegality. Morán placed a life-sized photo of a gang member with a hole where the head should be, inviting passersby to stick their own heads in and take photos of themselves as if it were a tourist attraction. The apparent banalization of the gang theme-it has become both a stigma and an image of desire-is essential to this piece.

Other essential themes present in the exhibition are foreign influence (Jabalina by Mauricio Miranda), the basic right to sustenance (Copyright by Lucía Madriz), domestic violence (Lección de maquillaje by Priscilla Monge or Mi dulce niñez by Ronald Morán), the discrimination of the indigenous population (Sin título, Eduardo Chang), and an economy sustained by foreign remittances (Líneas de desplazamiento, Mauricio Esquivel), among others.

R.C.- Given the context in which these works emerge, do you believe that these proposals awaken the social conscience? To what extent do they affect the average Central American?

C.A.- Art has historically been a part of political resistance in regions such as Central America. Figures from Luis Cardoza y Aragón in Guatemala to the Salvadorean Roque Dalton were political exiles at one time. The great regenerative movements in Central America have emerged from the field of art. The best example would be Caja Lúdica in Guatemala, a project directed by the artist José Osorio, who proposed artistic production as a form of dialogue and healing in the indigenous zones and populations and urban groups most affected by the postwar years. Art has started to generate a less stereotypical image of the area, exploring the different shades of violence, its causes, effects, and possible means of healing.

Guatemala, for example, has more missing persons than Argentina. However, due to its high percentage of indigenous people and the lack of sufficient resources and significant local cultural industry, this problem has not had as notable an impact in film or in other artistic practices as has been the case in Argentina. El Salvador, which is part of this Mayan belt between Honduras and Guatemala, has almost no indigenous people; they have been massacred.

Since the end of the 1980s, art has once again placed this agenda on the table for discussion. To this we can add the work of young artists-sometimes identified as the postwar generation-who work from a neoconceptual perspective and for whom the investigation and social repercussions of violence are crucial.

Let us consider that a hallmark of this region’s contemporary art is communal work. Nevertheless, it is difficult to know how much it is influenced by the people and to measure this impact statistically. Luis Camnitzer, in his pedagogic curatorship work, always points out that if an exposition changes the life, actions, or thoughts of only one person, the artistic exercise is effective. Central American art also changed us a little, not only as professionals, but also as individuals, and that is replicated in the people we know. The same thing happens in the artists’ communities. The significant thing is that the most vital visibility strategies of Central American art have undermined the exhibition space and have spilled over into public space, being aware that the model of the enclosed institution is not effective for such practices. The performances of Regina Galindo, Aníbal López; the urban projects of Walterio Iraheta, Yamil de la Paz, Mauricio Miranda; and the communal works of Alicia Zamora, Ernesto Salmerón, and Caja Lúdica, among others, are explicit examples of this modus operandi.

R.C.- This exhibition was presented at arteaméricas for only four days, but it would be great if it could be shown for a longer period of time in a museum or cultural space. Do you have plans for this exhibition to travel to other cities?

J.B.-The presentation at arteaméricas functioned as a precursor to the project. We are now in discussions with various institutions that have offered us their support so that we may jointly present the exhibition in its totality. There are significant pieces coming from museums that we were not able to include in this first exhibition. We foresee a program of performances that will summarize the prominent role that this exhibition has had in the area, along with photography, video, and installation. We also want to prepare a catalogue to accompany the event, in which other voices can be included that have been crucial within the study and appreciation of Central American art, like Virginia Pérez-Ratón and Rosina Cazali.

It should travel to other cities in the United States and Latin America because the purpose of this exhibition is precisely to tear down preconceptions with respect to the foreign-held view of the region and to give recognition to artists from this region who are structuring very contemporary discourses.

For more information, contact jbatet@hotmail.com

Raisa Clavijo is an art historian, curator and art critic based in Miami. She is founder and editor of ARTPULSE and ARTDISTRICTS.