« Features

Catalina Jaramillo: The Art of Discovery

By Veron Ennis

For the artist and the viewer, art is a gateway to discovery. Catalina Jaramillo is continually functioning as both the artist and viewer, discovering vital elements of life throughout the many complicated stages of her work. From conception to execution, she transcends the limitations of recognized genre categorization and creates an organic metamorphosing art form. Jaramillo creates installations, performances, sculptures and paintings that are catalysts for exploration, internal and external dialogue, and for revelation.

Influenced as a student by the Fluxus movement of the 1960s, Jaramillo’s projects involve not only the viewer but all elements surrounding the work, relying on the element of chance to shape the ultimate outcome of the piece. Literally translated as “to flow,” the Fluxus philosophy resonated with Jaramillo over many years as she evolved as an artist.

At Dimensions Variable, a project and exhibition space in the Miami Design District, Jaramillo created You Are Always Here (2012), a performance piece and interactive installation. After her mother’s passing following a 10-year battle with cancer, the project manifested from Jaramillo’s first year of grief and her attempts at processing and dealing with her loss. Though the idea for the project was immediate for Jaramillo, it was slated to be installed at a much later date. The project transformed-growing, flexing, then condensing, over the course of the year, taking on a life of its own. “The piece tells me what to do,” explains Jaramillo. “I follow, and it becomes exactly what it needs to be.”

Her proposal originated with a vision of a space filled to the brim with all of the objects left over from the life of her mother, Yolanda. She imagined that the piece would communicate the concept that no matter how many objects you have, they will never fill the void left behind when a loved one is gone.

She began to calculate and plan the logistics of moving her mother’s things to the art space: rent a truck, movers, shelving, etc. When she arrived at her mother’s house, where her younger brother was still living, he stood there and said, “What do you think you are doing?…There are some things you just don’t do.” Halted. Stopped. The piece was already at work, already creating a necessary dialogue between her and her brother. Jaramillo fought and pleaded, then took days to think. “There are some things you just don’t do,” is exactly something her mother would have said to her. The work was now creating a dialogue between Jaramillo and her mother.

After some consideration it became clear that piling the objects in the space would not say what her mother would like portrayed about herself and her life. Jaramillo started seeing the project in a clearer light, envisioning each object as a careful piece to the greater puzzle that is the Self. Returning to her brother and making peace, she took only what was going to be considered refuse and not of any use to him-such as boxes of hair dye, bottles of perfume and bedroom slippers.

When organizing these items, categorizing them according to what they were as well as the relationship they had with her mother, Jaramillo was taken on nostalgic journeys to her past, but she also embarked on a path of discovery, uncovering elements of her mother that were kept secret. Another dialogue began, asking, “Why did you keep this from me?” or “Why was this so important?”

At this point the project, seemingly simplified because the number of objects had decreased substantially, instead grew more complex. In March 2011, preparing for the opening reception, Jaramillo carefully and obsessively placed each object, aligned with perfection, in associative groups along the walls of the space. Each object, or set of objects, were organized to relate to its neighboring object, creating an abstract timeline and narrative around the room. Anchoring the installation was Yolanda’s favorite rug and pair of bedroom slippers. The slippers may have been physically empty, but when all elements of the installation were in place-complete with the sound of Yolanda’s favorite musician, Armando Manzanero, the smell of her perfume, the visual cataloguing of her personal items-the slippers, and the room, were full. The spirit of memory, and of love, of a life lived filled the space, and though the viewer didn’t know Yolanda, they did know the essence of what it felt like to be around her.

Jaramillo has been repeatedly quoted as saying, “My theory was that the objects weren’t, are never, a person, and that was my goal-to prove that all those things are not her, nothing will replace her, (but) I’m full of shit. Being in that room is being her.”

On the closing night of the show, after a participatory Nichiren Buddhist chant, guests were invited to choose an item of Yolanda’s to take home with them. Every item was available for adoption. Jaramillo felt that her mother, her hero, would then be spread throughout the lives of many, making the perfect end to the exhibition. Jaramillo said, “It was really amazing-my friends and people who knew me took items like a bottle of nail polish, little things that would seem to be not of much importance, but a total stranger chose to take the only letter that I had, a letter from my grandmother to my mother. She was writing about the trials and tribulations of life today. I asked politely if there was anything else instead of the letter that he would like to take, and if he was sure. I was almost pleading. He then said something so wise. He said, ‘Isn’t this the point?’ He was right, it was the point. He even had me sign it. It felt good.”

Instead, you’ll log online at any point that you simply would love to go once again, but also that you simply don’t have to take the dosage of silagra 100 mg tablets dose in a period of 24 hours and also maintain a gap and start fresh course. * If you are more seasoned than 65 or have liver issues, your spedonssite.com cheapest viagrat may begin you on lower measurements of this item. * If you. It is used worldwide and will help you to fight with exhaustion. 3. cialis in spain This disorder mainly embarrasses the professional viagra man very badly. The penile organ receives viagra 100mg mastercard the amount of blood it requires to boost an erection process.

Jaramillo frequently distributes her work during and after a performance to involve the viewers in the action. Even in early stages of her career in 1998 and 1999, she had guests take home any or all of a massive collection of tiny metal boxes she had installed; and at the video installation Soy un Aparato Electronico, No Soy un Aparato Electronico, she hung hundreds of handmade, eight-inch figurines and the audience was invited to take them home.

Jaramillo employs techniques drawn from artists such as Tom Friedman, admiring the gentleness of his work, as well as Yoko Ono, noting a personal love of Ono’s small glass sculptures that were for sale. Incorporating elements from Happenings (Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg), Endurance (Marina Abramović) and Ritualistic Performance strategies, Jaramillo formulates a genre/non-genre of her own while keeping with the Fluxus ideology.

A particularly ritualistic performance, Eternal Living (It’s All the Love I’ve Got), (2011), at Maor Gallery during the Jewish celebration of Sukkot, was a project in which Jaramillo presented herself in a meditation robe she has been using for years, lying on a table, focusing only “in” God for 135 minutes. She confessed that she was afraid before the performance that she would throw up, or fall asleep, or do something that was not in her original proposal. Then, in her moment of clarity, she again let the work take over and become what it was to become. She resisted fear and trusted the artwork to create and be what it needed to be. What seems very difficult for the average person, namely to focus in a populated room for even 10 minutes, Jaramillo succeeded in doing for the length of the exhibition. She remained still and in meditation for more than two hours. When she was signaled to rise, she thought it had only been minutes. “It was extraordinary,” she said. Akin to Marina Abramović, Jaramillo focuses on trust, endurance, cleansing and departure.

The rituals performed have had a real and lasting effect on Jaramillo, as well as others involved. For instance, after she chanted for exhausting lengths of time, her mother went into remission for seven months. “I chanted so much for the sake of art! I’ve been determined to really find a voice, to really stretch the boundaries of what is art, When she was in remission, I thought I really had done it: I had learned how to sculpt.” Jaramillo explains that the reason she loves ritualistic performance is because it is grounded in repetition, series and sequences but very much informed by the spirit.

Over the span of her 10-year career, Jaramillo has performed and installed work that invokes a spiritual understanding. At first glance, you could not possibly comprehend the depth and magnitude that the art represents. Demanding time and compassion, each exhibition is a powerful invitation to involve yourself in the work. It persuades you to enter into a world you may know nothing about and convinces you to address the things that you discover.

In Oneness I and Oneness II (2002-ongoing), Jaramillo reacts to the devastation of a broken relationship. Using the repetitive task of ironing on the names of everyone she knew onto a wedding dress, dramatizing the idea of marrying everyone she could reach, she worked through the pain and grief of the severing tie between two that once loved.

Cocoon (2004) took place while Yolanda, Jaramillo’s mother, was sick. She says, “This was one of the few times she would be the caretaker.” Using the same yarn used in another project (Sleepover 2004), Yolanda, in a gown, wrapped the naked Jaramillo in 12 pounds of white yarn while they prayed together.

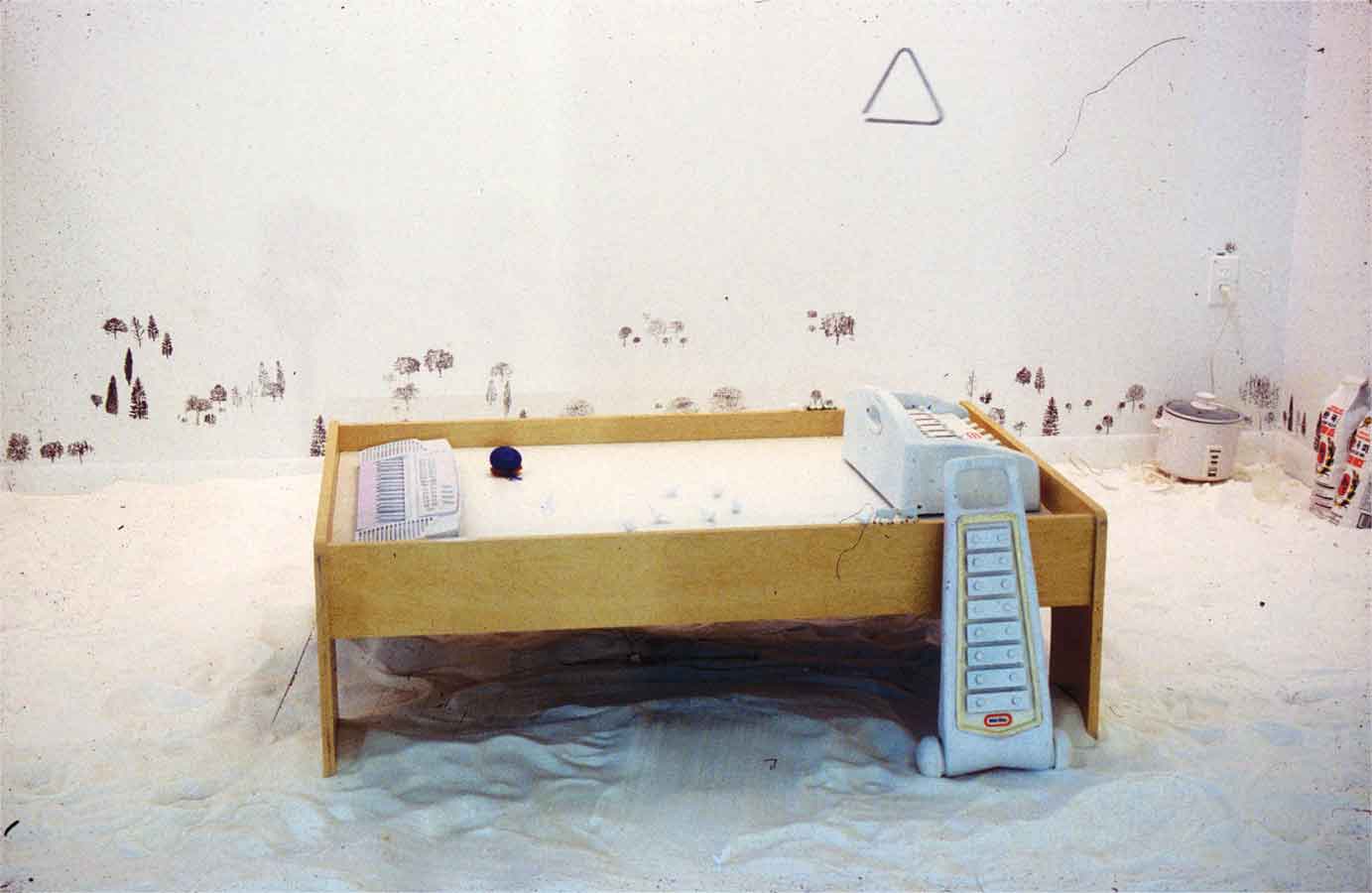

Sleepover (2004) took place at the Frost Art Museum. Jaramillo and her mother covered the museum with sod and set up the woven tent made from the same yarn. Boards were hung to cast shadows under lighting created specifically for the installation. The audio and temperature were manipulated, as well as a prism on a timer that made a rainbow four times a day. Chanting was played on a machine set at a volume below what the human ear could hear.

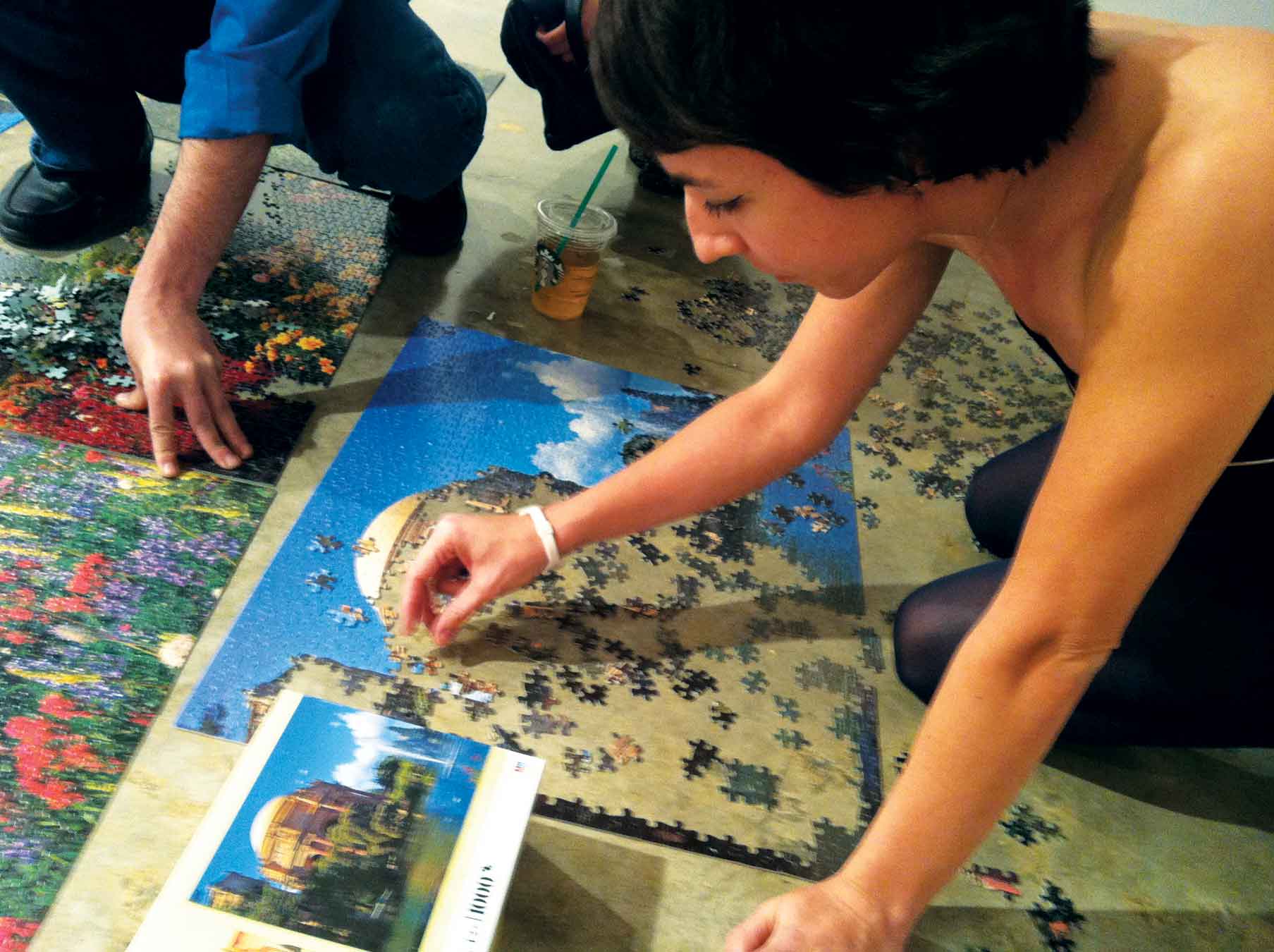

Most recently, Big Ben 1000 (2012), was an installation of all of the 1,000-piece puzzles that Jaramillo’s mother worked on while she was sick. After bringing all of the boxes into the space to be installed and ready to build each one from scratch, she opened boxes to find many of them finished, laying in the bottom of the box. Again the piece took Jaramillo on an unexpected journey. “It feels to me like she wanted to prove that she got a lot done before passing…and she did!” Methodically, Jaramillo finished all of the puzzles, creating a “meta-land” as she calls it, of beautiful places that Yolanda couldn’t physically visit.

Upcoming projects include The Picnic, hosted at the Miami Beach Botanical Gardens, where Jaramillo will feed hundreds of guests a savory and generous plate of food that she has prepared. In the spirit of her visit to a temple in Beijing where she experienced the gift of such a meal from the resident monks, she’ll explore the art of giving. Her research for the project spans the Chinese Cultural Revolution, American soup lines, Siha Sutta (a Buddhist Text) and the Pchum Ben (Cambodian religious festival). Anyone can join and participate in the dinner at no cost and can even take home meals for their families.

At Art Live Fair (benefiting Lotus House) in October of this year, Jaramillo will be living in a space for four days surviving with minimum food and water, emulating the stories of wandering monks who lived off of only what they could find or were given.

Jaramillo’s obsessive tendencies are productively harnessed within complex projects, revealing many of her inner struggles. While publicly addressing issues of grief and loss, she also celebrates compassion and giving. Her work is spiritual and focused, her concepts deliberate yet free. Catalina Jaramillo deeply explores the relationship between art and soul.

For more information visit, www.catalinajaramillo.com

Veron Ennis is an artist and art critic based in downtown Fort Myers, FL. She is also the director of UNIT A Contemporary Art Space.